This article was originally published in the Fall/Winter 2019 issue of The Newberry Magazine.

The Newberry’s Edward E. Ayer Collection of American Indian and Indigenous studies includes one of the world’s greatest collections of books documenting the Indigenous languages of the Americas.

Of the many strengths within the Indigenous linguistic material, one of the most remarkable is the vast collection in the Nahuatl language. Nahuatl remains one of many Indigenous languages still spoken in Mexico and Central America today. (A total of 11 Indigenous language families, with 68 Indigenous language variants, are still spoken throughout these regions.) The Nahuatl language is part of the Uto-Aztecan language family and consists of many regional variants; it is related to the Hopi, O’odham (Pima-Papago), and Tongva, as well as many other Indigenous languages.

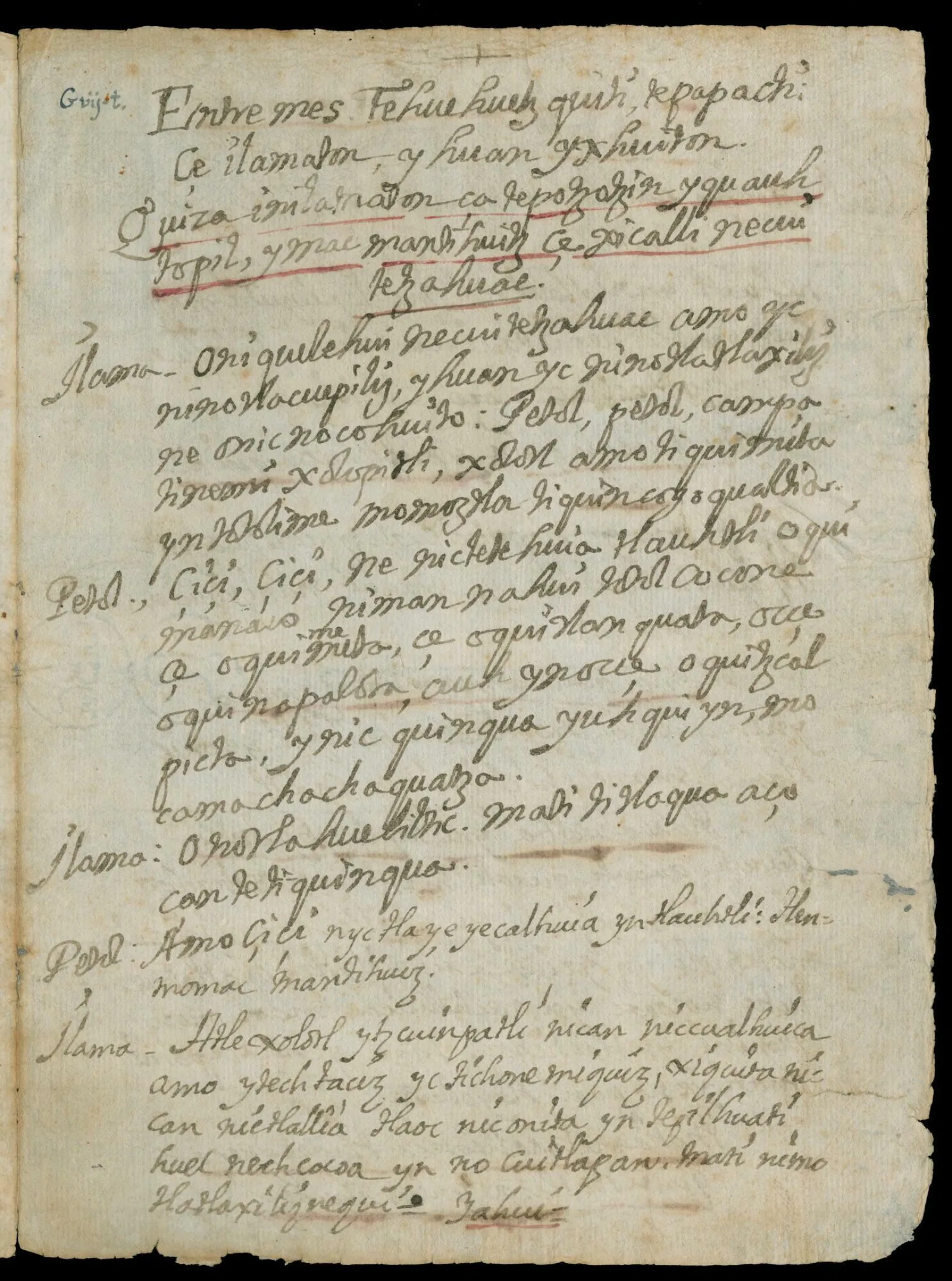

In 2018, the Newberry acquired a notable addition within its American Indian and Indigenous studies collection: a short comedic play in the Nahuatl language, written sometime between 1650 and 1750 in Huejotzingo, Mexico, which then fell under Spanish colonial rule.

The anonymously written play, possibly by an Indigenous author, presented a challenge for us to read and transcribe because the author tended to write the words so closely together. (The play does not have a standard title, though it is sometimes informally called The Old Lady and Her Grandson, or Ilamatzin ihuan ixhuiton in Nahuatl.) An initial description of the play characterized it as a short farce featuring two characters: "ce ilamaton" (elderly woman) and her “incompetent” grandson Petol (likely a Nahuatl version of the name Pedro).

The plot is quite simple: the elderly woman looks forward to tasting some honey that she has purchased, but she never gets a chance to taste it because Petol eats all of it. The comedy ends with the elderly woman denouncing Petol’s gluttony. This short and very funny play consists of only three small pages.

Our research about this play led us to a 1948 publication by ethnographer and historian Fernando Horcasitas. According to Horcasitas, the play chronicles the story of a grandmother who leaves her grandson to watch over their turkeys while also telling him to keep an eye on a jar filled with a mysterious liquid. She tells her grandson not to drink the liquid and warns him that, if he does, he will become sick. The jar contains necuitetzahuac (a special kind of potent pulque, an alcoholic drink made by fermenting sap from the maguey plant). After the grandmother leaves, her grandson gets very hungry and drinks the necuitetzahuac, becoming drunk. He then believes that he has been transformed into a coyote and begins to howl. When she returns, the grandmother scolds him, and the play concludes with them dancing as they exit.

Most plays written in colonial Mexico during this era drew on religious ideas, but this play instead stands out for its secular themes. Catholic priests viewed the Nahuas’ devotion to their deities as threatening, and wondered how they could convert them to Christianity. They turned to traditional performances that had developed in Europe during the Middle Ages, some of which became quite popular in Mexico after its conquest by Spain. Most of these religious plays found inspiration in the Bible or from saint’s legends and often had a moral at the end. In colonial Mexico, they became a tool for conversion. This play in the Newberry’s Ayer Collection, however, does not fit the pattern.

The Mexican philologist, linguist, and scholar Fray Ángel María Garibay Kintana noted our Nahuatl play’s connection to the Indigenous tradition of pre-Hispanic theater. A central element of this tradition is the figure of the truhane, a person who scams others through disguise, cunning, and playfulness. Petol is a version of this figure. Disguised as an innocent grandson, he turns out to be the truhane, “scamming” his grandmother into believing he was going to watch her drink and her turkeys. Other unique Indigenous elements within this short play include the guajolotes (turkeys), the coyote, the necuitetzahuac drink, and Petol’s playful, childish nature.

Though information on the play’s reception is difficult to find, it might have been intended for a general audience. The play starts with: “Entremés. Tehuehuetzquiti tepapachi,” which roughly translates to: “A performance that makes a lot of laughter that enjoys several reprises.” An “entremés” is a short, comic theatrical one act, usually performed during the interlude of a long dramatic work, during the 16th and 17th centuries in Spain.

Aside from a French translation published in 1900 and a Spanish translation published in 1946, the play has not been studied by modern audiences. Based on preliminary research, I believe that the manuscript now in the Newberry’s collection may have been part of the private collection of Francisco del Paso y Troncoso, the Mexican historian, archivist, and Nahuatl language scholar. Since the French translation’s publication in 1900, the manuscript seems to have been unavailable to scholars and the public until it came up for auction in 2018.

Now that the manuscript is in the Newberry collection, our colleagues, working alongside Nahuatl expert Victorino Torres Nava and Abelardo de la Cruz of the University of Albany, have been able to transcribe the work into Nahuatl, translate it into English for the first time, and digitize it.

Additional Nahuatl-language materials held at the Newberry include some of the first grammar books and dictionaries ever printed on this continent, as well as other manuscript material. The newly acquired play is not the only Nahuatl play in the Newberry’s collection: our [Manuscritos en mexicano], which date from 1855–56, include three copies of miracle plays in Nahuatl and Spanish, translated by Faustino Chimalpopoca Galicia: Las almas y las albaceas (The souls and the executors); Nacimiento de Isaac (The birth of Isaac); Sacrificio que Abraham su Padre quiso por mandado de Dios hacer (The sacrifice that Abraham his Father wanted by command of God to do); and Maquiztli: tragedia escrita en idioma mexicano (Maquiztili: a tragedy written in the Mexican language) by Mariano Jacobo Rojas with a translation in Spanish by Pedro Rojas. The latter is a tragedy in which Prince Quillotl, defends Princess Maquiztli from a Spaniard and dies. In response, Maquiztli commits suicide.

The United Nations declared 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages, highlighting their importance and vitality as well as their increasing endangerment. There are approximately 6,500 to 7,000 languages spoken throughout the world today. However, in 2016, the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues determined that 40 percent of those languages were losing more speakers than they were gaining. This decreasing population of fluent native speakers of Indigenous languages results directly from several historic assimilation and education policies that denied rights to different minority linguistic communities. No public policies exist to help develop learning and use of native languages among Indigenous populations.

Yet, in spite of the genocidal consequences of settler colonialism in North America, many Indigenous peoples have preserved their languages. Many variants of the Nahuatl language are still in use today, especially in regions from Nicaragua to Central Mexico. Improving access to unpublished works such as this comedic play should help shed light on the diversity of Indigenous languages in Mexico, while also opening up opportunities for reinterpreting historical works from a contemporary perspective.

Making sources of Nahuatl language and culture more widely available to Nahuatl speakers may also mark a small step toward reconciliation between institutions rooted in colonial history (including many libraries and archives) and Indigenous communities. Connecting communities with their histories can enable the strengthening of Indigenous identity and help to grow networks of Indigenous language speakers in Mexico, El Salvador, and Nicaragua, as well as in Nahua migrant communities throughout the world.

Analú María López (Guachichil/Xi’úi) is the Ayer Indigenous Studies Librarian at the Newberry. Victorino Torres Nava (Nahua) is a native Nahuatl speaker and linguist; a professor at Anahuacalmecac School in Los Angeles; and founder of the Xinachkalko Center in Cuentepec, Morelos, Mexico. Thank you to Abelardo de la Cruz (Nahua) of the University at Albany, a native Nahuatl speaker, for his work transcribing this manuscript.