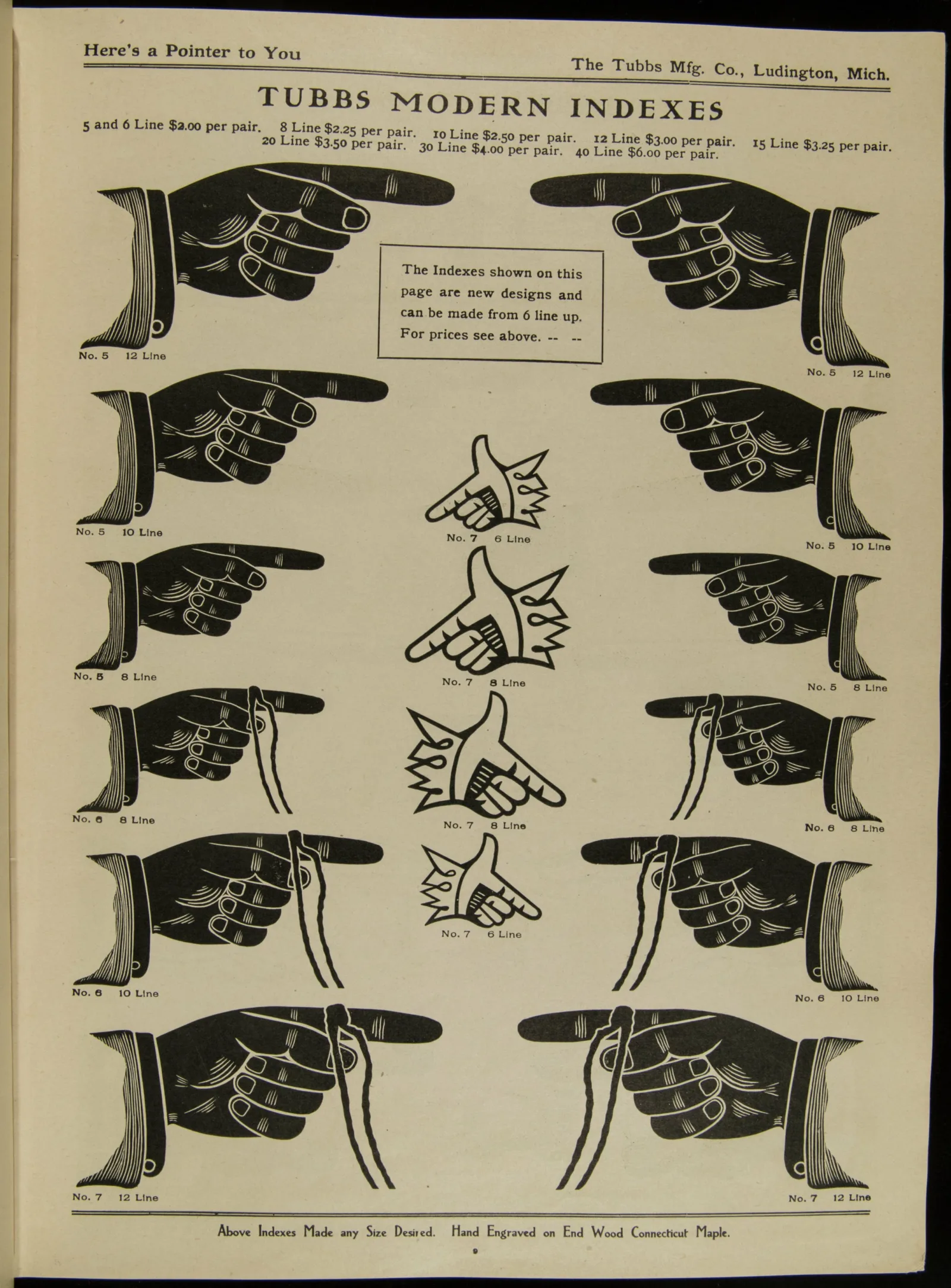

You might not know what they're called, but odds are you encounter them all the time: those hands, with their index fingers confidently extended, pointing you in the direction of a nearby restaurant, record store, or antique furniture shop. These icons are manicules. Redolent of the age of Buffalo Bill and P. T. Barnum, today they are mainstays of the visual lexicon of advertisers, graphic designers, and restaurateurs going for self-consciously ironic kitsch.

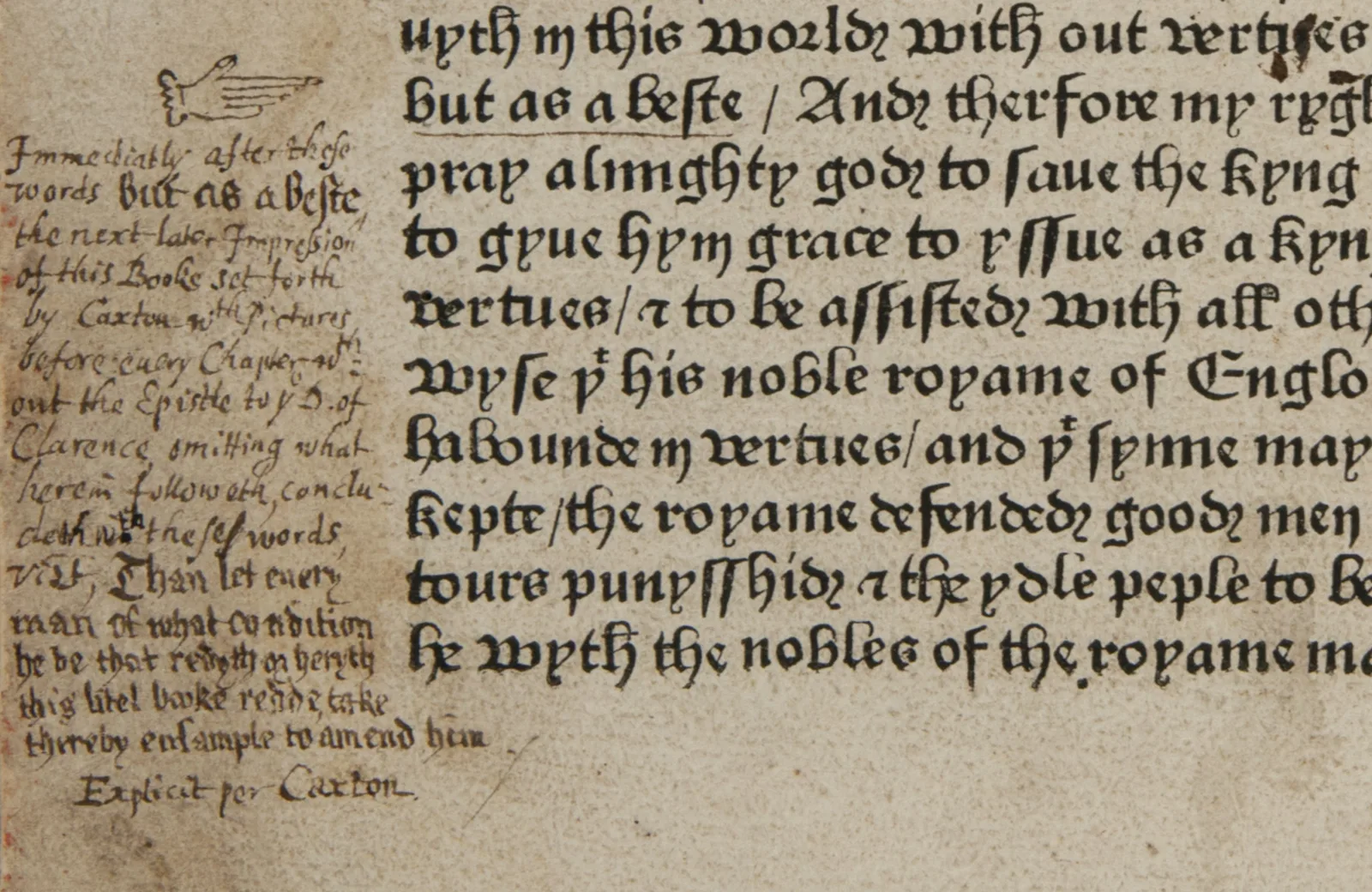

The manicule's origins, however, can be traced much farther back in time, when readers used it to mark private moments of joy, curiosity, wonder, disagreement, outrage in the margins of their books and manuscripts. Manicules were ubiquitous long before they crawled onto awnings and billboards. According to William H. Sherman, one of the foremost experts on the manicule and marginalia in general, “between at least the 12th and 18th centuries [the manicule] may have been the most common symbol produced both for and by readers.”

The Newberry's collection is uniquely positioned to document the manicule's evolution from marginal sign post guiding a single reader's textual experience to promotional flotsam directing the public’s commercial activity. With collecting strengths spanning the centuries before and after the invention of the printing press, the Newberry harbors manicules in a variety of manuscripts, printed books, and type specimens.

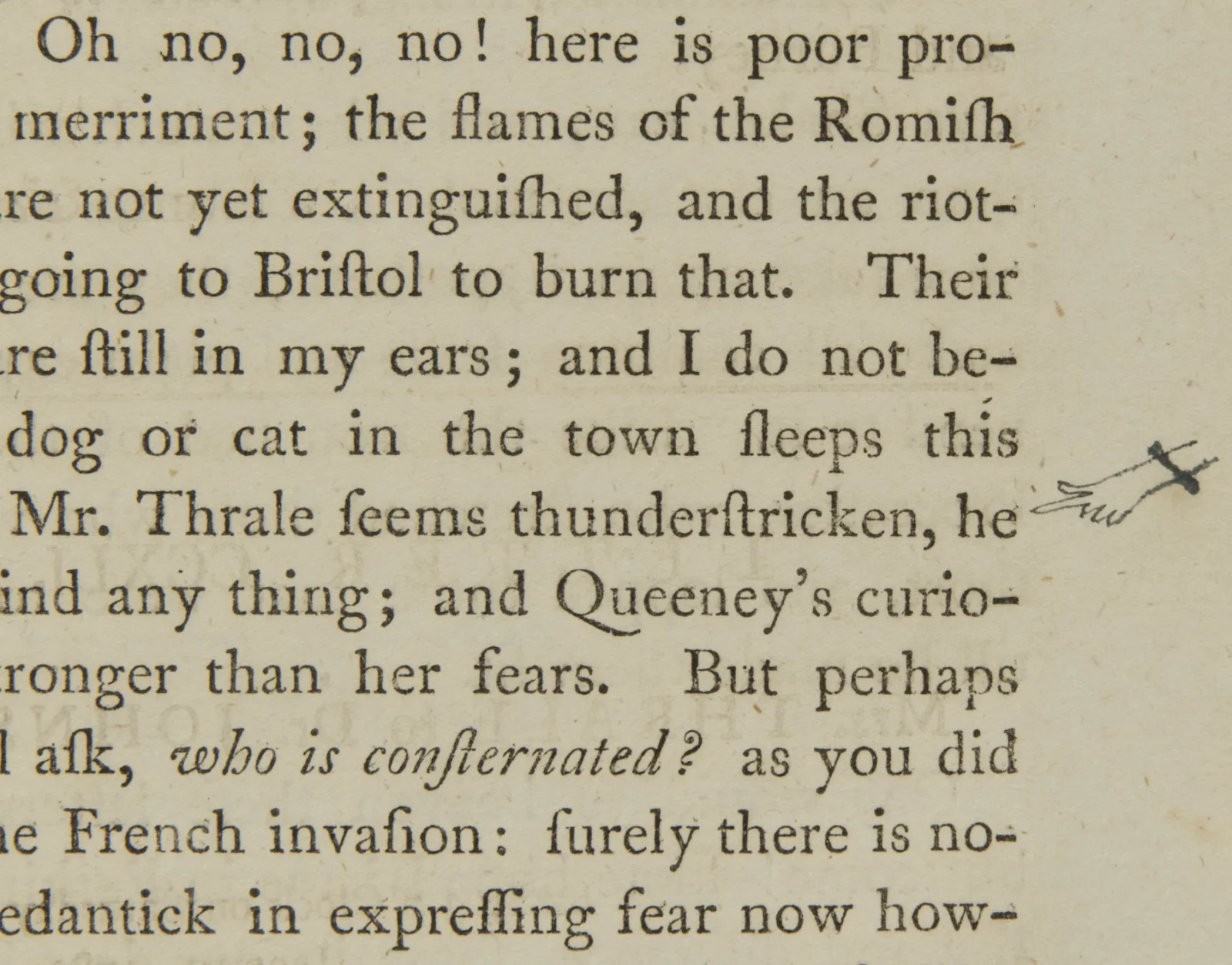

Manicules came in all shapes and sizes, encompassing the anatomically exact, the cartoonishly distorted, and everything in between. And whatever their form, they defiantly persisted long after the invention of print and the organizational conventions (paragraphs and chapters, e.g.) that would seem to have obviated the need for readers’ markings.

“Some preprint practices passed to readers in the age of print…and no doubt helped them come to terms with the new medium by marking its products with traditional features,” writes Sherman in Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England.

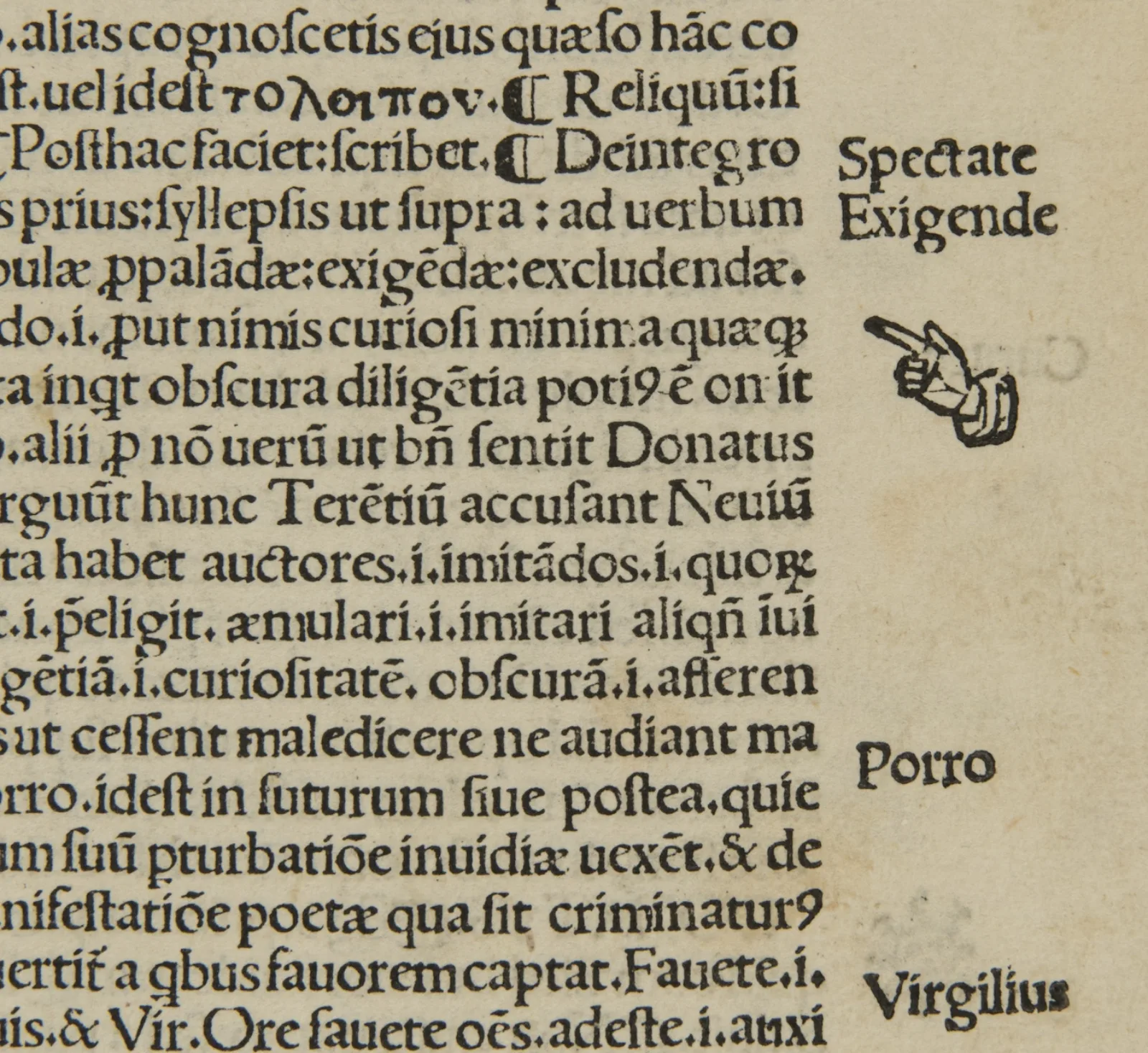

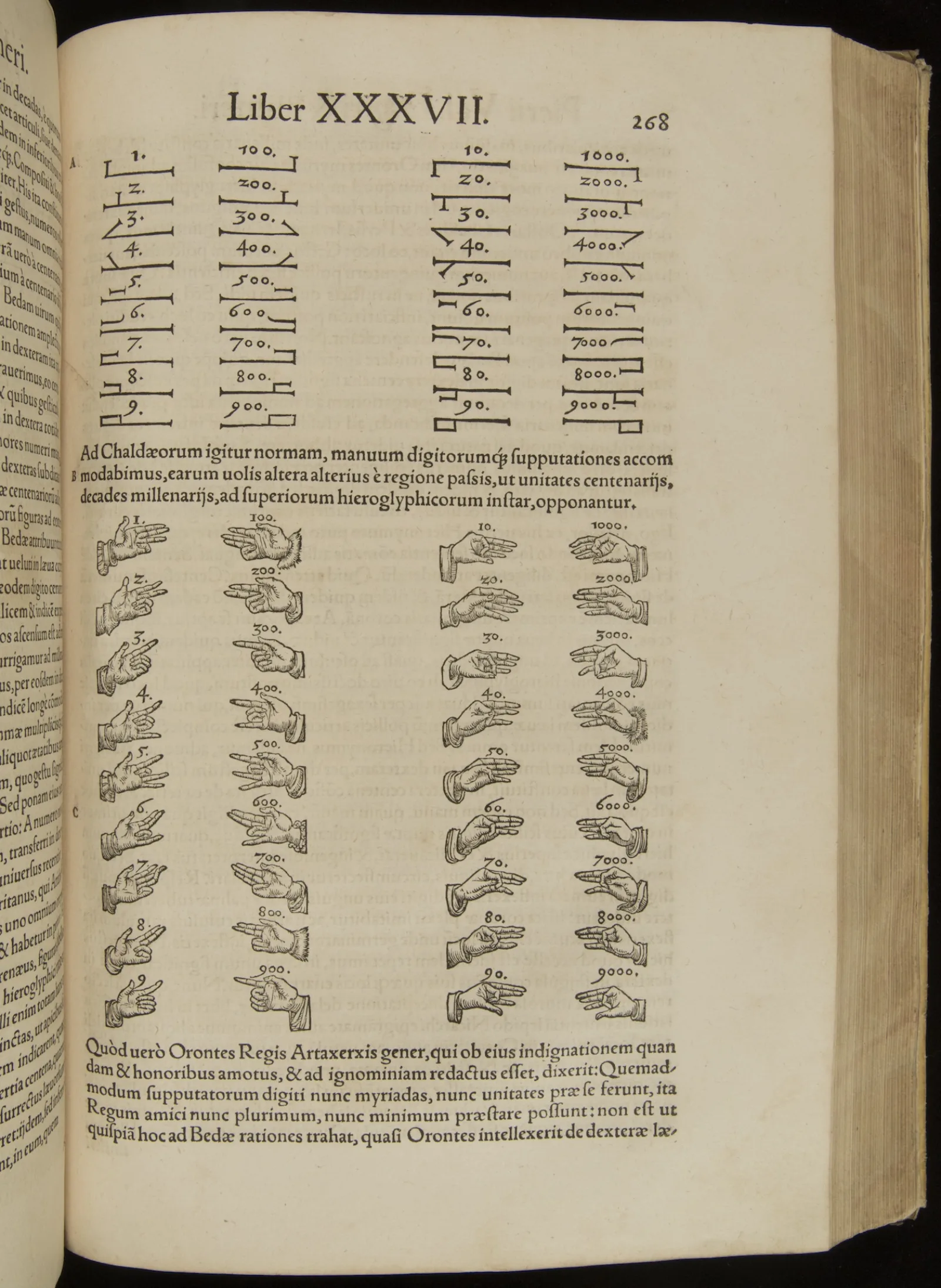

Readers’ manicules even coexisted with the printed manicules Renaissance publishers used to signal the relationship between a text and the scholarly commentaries included in its margins. In the emerging and competitive European book market, booksellers touted such added pedagogical value; and so manicules, with their centuries-old association with knowledge, became a feature of books that claimed to confer it.

This connection between hands and knowledge has an ancient legacy. As Sherman notes, Quintilian’s Institutio oratoria divided the subject of “delivery” into “utterance” and “gesture,” and went into great detail about how hands may convey meaning. The hands-knowledge nexus is encoded in the English language even today. We grasp concepts; point out noteworthy features; grapple with difficult ideas; touch on important information.

Printed manicules appeared not just in the margins of Renaissance books but on their title pages as well, drawing readers’ attention to introductory information as a way of preparing them for the text they were to encounter. According to Keith Houston in Shady Characters, these manicules serve as the most direct forebears of the promotional hands that appeared in public spaces throughout the 19th century and up through today.

Ironically, manicules now draw as much attention to themselves as to the things they point to, shorthand that they’ve become for an ineffable past we’re constantly reaching for.

About the Author

Alex Teller is the former Director of Communications and Editorial Services.