Amate or amatl is a form of paper created from the inner bark of a wild fig tree. The practice of harvesting the bark to make paper dates back nearly 2,000 years and has been used by several Mesoamerican societies including the Maya, Aztec, Toltec, Zapotec, Mixtec, and Otomi peoples. The earliest known examples of amate being used for mapping is dated to the fifth century CE.

As scholar Barbara Mundy noted in 2022, “amatl paper was more often used in rituals than for manuscripts—burned to carry blood offerings to deities, or used for the costumes that would convert human actors into embodiments of the gods.” In colonial Latin America, paper production was a site of tension between Native cosmological (re)production and Spanish censorship and reeducation. Amate papermaking was largely banned and replaced with European paper after the Spanish conquest, but the production and rituals of amate were not completely wiped out.

The Newberry Library has several Mesoamerican paper types in its collections. One such item is Bernardino de Sahagún’s collection of sermons written in Nahuatl (VAULT oversize Ayer MS 1485). Originally thought to be composed of amate, the manuscript was submitted to chemical analysis which revealed that it was made of forty-nine sheets of the much scarcer agave fiber paper called maguey. This item is perhaps the largest extant collection of maguey in the world. The manuscript’s use of culturally significant paper and the implementation of the Indigenous language was an attempt by de Sahagún to more effectively convert Native peoples to Christianity.

During the recent 2025 Nebenzahl Lectures in the History of Cartography, the Newberry hosted Papel Amate Workshops led by Chicago-area artists Aidan Anne Frierson and Michael Baja Anderson. The workshops sought to underscore the labor, materiality, and significance behind an ancient creation used by several Mesoamerican cultures.

Participants in the class received hands-on training in a contemporary adaptation of amate production. The bark was pre-harvested for attendees. Strips of bark five feet long and one inch wide were stored and soaked in buckets of water, softening the fibers and making the material malleable. Instructors took out clumps of the bark and set to untangling, straightening, and cutting the bark into paper-sized strips.

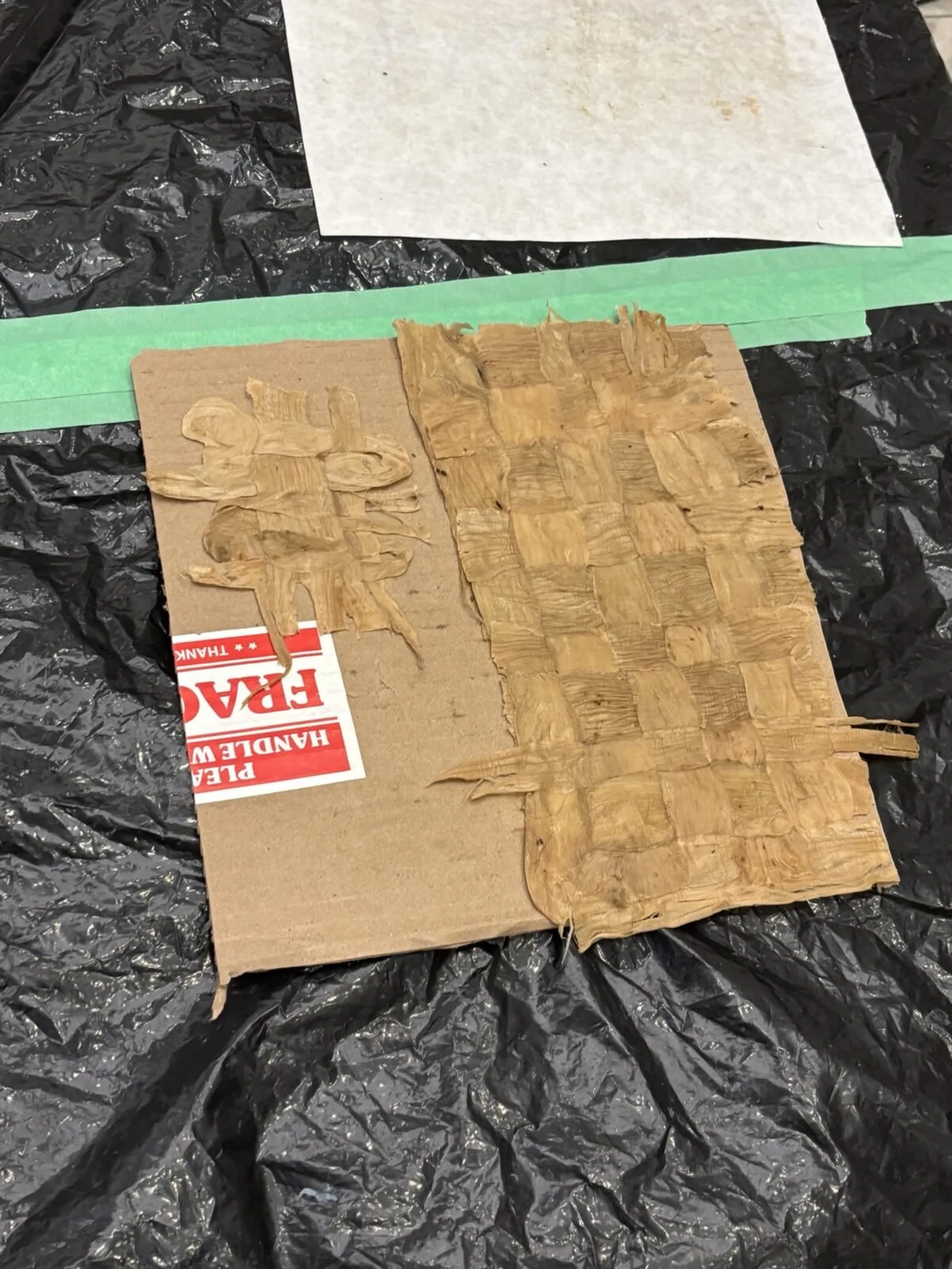

Then the participants took over: first, laying out their strips vertically or horizontally defining the first dimension of their amate’s width or length.

Next they began adding a second layer of bark perpendicular to the first layer. This was done by folding back every other strip of the first layer of bark, laying down a strip for the second layer and then laying the folded bark back over the newly placed piece. This process was repeated until the two layers covered the desired size for the final paper. Then the excess fiber was trimmed from the edges. Interweaving the bark this way helps the fibers form a cohesive and strong bond during the next stage: mashing.

Participants were instructed to pick up a rock and to begin pounding the hatched bark in a quick, firm, and circular pattern. The ideal rock is one with a rounded side for gripping and a smooth, broad surface for striking. The flat striking surface ensures evenly distributed downward force that will cause the wet fibers to entangle with other strands above or beside them. The instructors informed the class that the arrangement and mashing of amate fibers was generally carried out by women in these societies, and most bark harvesting for amate was the responsibility of men. The mashing continues until there is no more space between the fibers and a single sheet is formed.

The final step was to place the amate on flat surface where it will eventually dry out and be ready for use.

Instructor Aidan Anne Frierson reflected on the workshop saying, “It was a sincere honor to share a contemporary method of making while honoring connections to the sacred practice of Papel Amate. We are so grateful to have been invited to participate in and facilitate such meaningful activation. One of the participants, a mother who came with her son, shared with us that this really meant a lot to her, noting that hearing the sounds of the stones coming in contact with the fiber and the boards instantly brought her back, bringing up memories of hearing stones pounding from the amate makers near her hometown in Mexico.”

Learn More About the Smith Center