Race is not a natural thing. It is a social construct—a product of cultural, political, and economic factors that shift and coalesce over time, creating hierarchies of power that affect people in real ways. In other words, race is something we make.

Tracking the long history of this process, which scholars like Noémie Ndiaye, Associate Professor of Renaissance and Early Modern English Literature at the University of Chicago, call “race-making,” is often dry and devastating at the same time. Much of the most painful archival evidence lurks in sterile bureaucratic documents. Over and over while curating the Newberry’s current exhibition Seeing Race Before Race, we confronted stories of shocking violence related through neat statistical records.

The Short State of Barbados and the Government Thereof, a 26-page administrative manuscript dating to 1684 that is featured in Seeing Race Before Race, coolly surveys the population and geography of the colony of Barbados, then under British control. “The Inhabitants of this Island are of four sorts,” the record notes, the first three of which are explicitly identified as “White” and “Christian.” These include:

- “Freeholders,” or landowners;

- “Freemen,” or former servants who have fulfilled their contracts of indenture; and

- “Servants,” or indentured workers.

As of 1684, these three “sorts” accounted for 19,568 total inhabitants on the island:

- 7,235 “White Men,”

- 3,687 “White Male children,” and

- 8,646 “White Women & Female Children.”

However, “the last sort” of inhabitants, according to the record, encompasses the largest population on the island: “Slaves,” or “Negroes brought thither from the Coast of Guiny [Guinea], Cormantine [in what is now Ghana], and Madagascar.” This dry language conceals a brutal history: human beings abducted across Africa, from Guinea in the west to Madagascar in the east, and trafficked across an ocean to labor in British plantations.

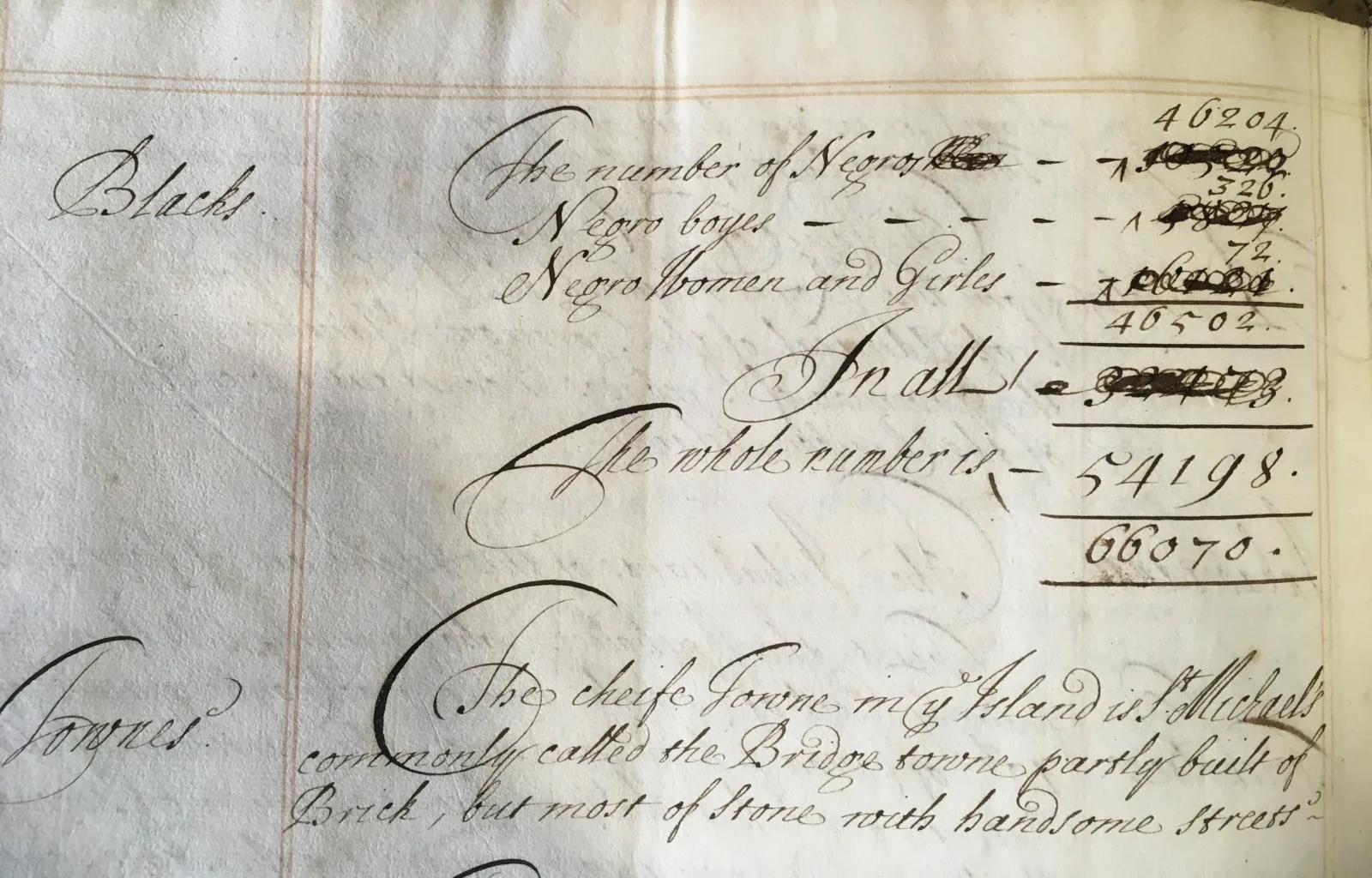

The statistical breakdown that follows further strips these people of their humanity. Instead of “Men,” “Women,” and “Children,” Barbados’s enslaved population is reduced to:

- 46,204 “Negro^s Men”

- 326 “Negro boyes”; and

- 72 “Negro Women and Girles.”

The category of “Men” has been dashed out here entirely by the manuscript’s scribe; “children” are not mentioned at all; and the number of enslaved female adults and children is alarmingly small, silently gesturing to the brutality that Black women and children must have endured. Overall, the numbers are staggering: enslaved Africans account for more than 70% of the colony’s total population.

Documents like The State of Barbados can be horrifying in their mundanity. After tallying the huge enslaved population, the record goes on to list the colony’s primary exports (ginger, indigo, cotton, sugar, etc.) and imports, which include tools for processing sugar, clothing, horses, and “Negroes from Guiny and other parts.” It’s easy for one’s eyes to slip over these details, to miss the stark evidence of race-making that reduces a whole population of human beings to “Commodities…Imported” alongside tools and household goods.

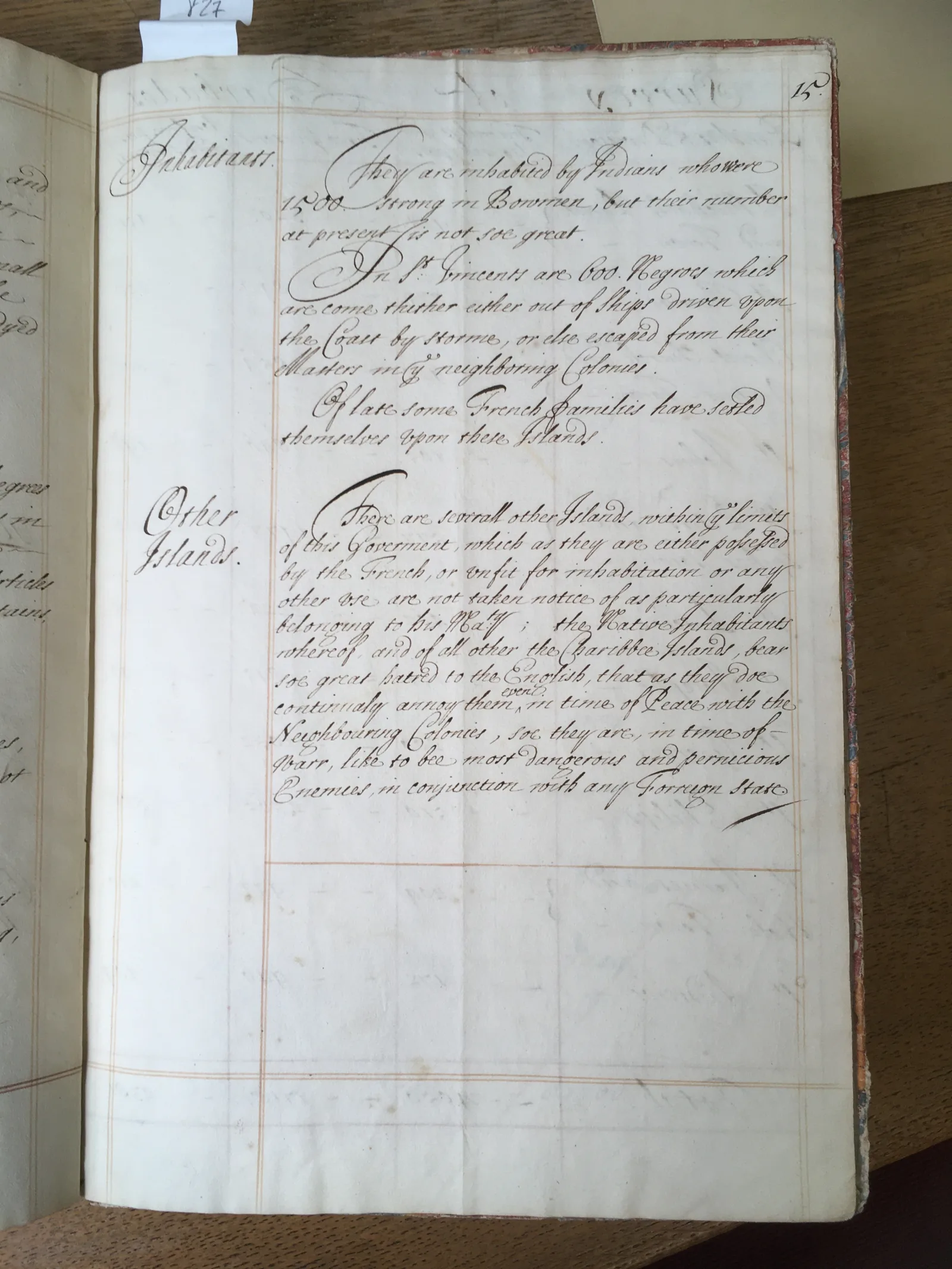

Yet records like this also tell stories of resistance, struggle, and liberation. Despite how the manuscript’s bureaucratic language seems to normalize the violence of colonization and enslavement, it also surfaces evidence that many people, especially Indigenous locals and trafficked Africans, fought back hard. After surveying Barbados’s population and economic interests, the manuscript goes on to describe several nearby islands, many of which are “inhabited by Indians” and “Negroes…come thither either out of Ships driven upon the coast by stormes, or else escaped from their Masters in the neighboring Colonies.”

Beyond hiding from English forces, escaped Africans and Indigenous communities waged war against them: “the Native Inhabitants….of all other the Charibbee [Caribbean] Islands…bear soe great hatred to the English,” the record observes, “that as they doe continually annoy” the colonizers, and are “like to bee most dangerous and pernicious Enemies[.]” In this short sidenote, we see hard evidence in the dry colonial archive that nearby Natives (and implicitly, escaped Africans joining them) despised the English settlers and constantly “annoy[ed] them”—that is physically attacked their ships and settlements. They refused to be erased and enslaved. They presented a danger to the colonizers who would reduce them to something less than human. They made the English afraid.

The State of Barbados is not unique in burying both the violent histories of enslavement and stories of fierce resistance in bureaucratic mundanity. Countless archival documents like this manuscript force us to confront the everyday legal and social decisions that make race and its attendant power structures seem normal and natural. But they also remind us that these structures are not natural. Race is a system of power that people actively make, and it has always been contested. Seeing the history of this system clearly, however painful it may be, can equip us to contest its injustices today as well.

Rebecca L. Fall is Program Manager for the Newberry’s Center for Renaissance Studies and a Co-Curator of the Seeing Race Before Race exhibition.

PURCHASE THE EXHIBITION CATALOG