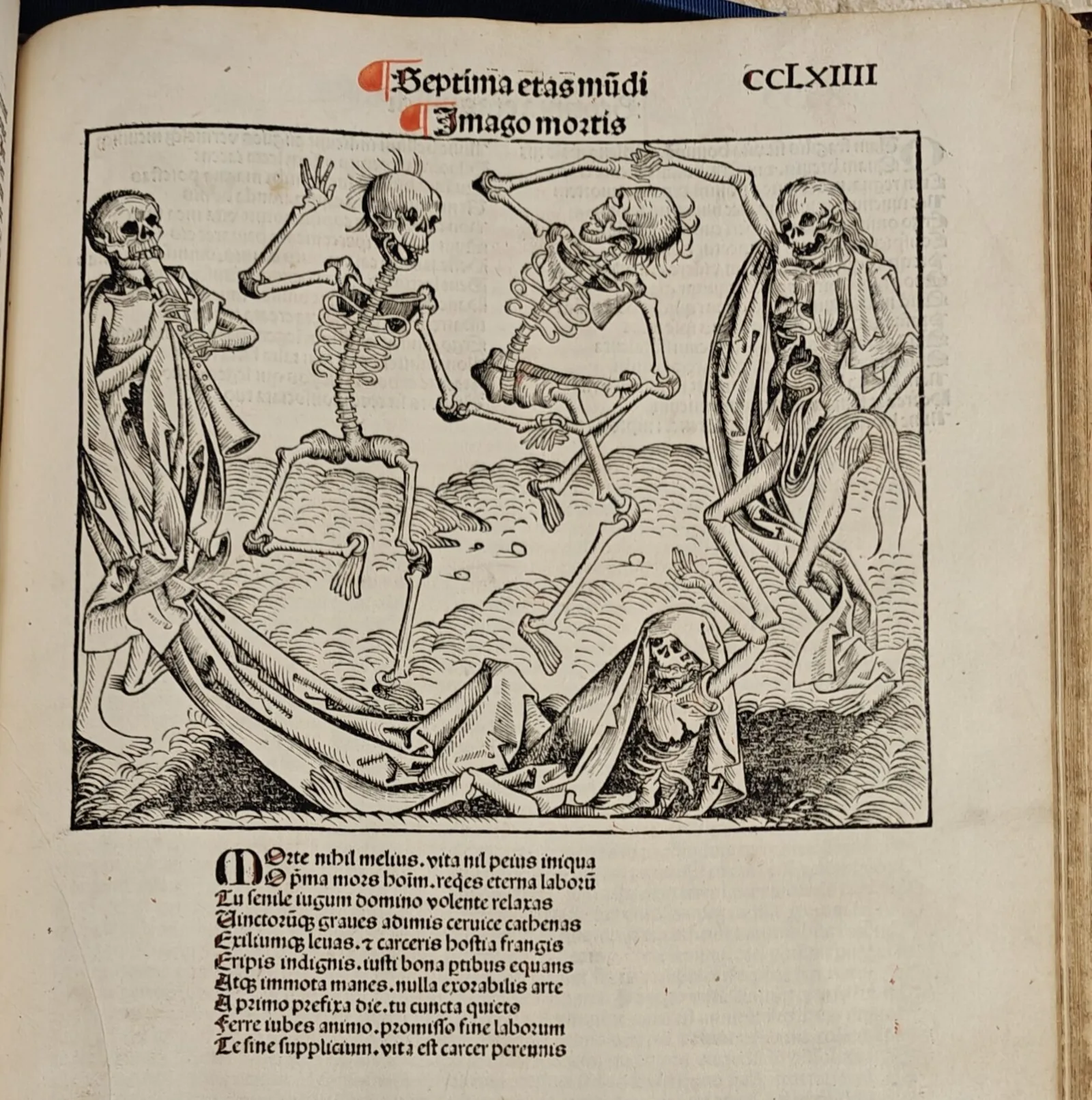

You may have already seen the Dance of Death, or Danse Macabre, but have you ever heard it? This morbid trope was incredibly popular with a Renaissance public fixated on the big issues: life, death, and how to expire the right way. Think dancing skeletons with jauntily dangling innards and leering, toothy skulls, all reminding YOU to live a good and moral life. While the concept predates the Black Death, the fourteenth-century bubonic plague Europe helped popularize its dramatic appearance in literary, visual, and even musical media.

While searching for skeletons in our proverbial collection closet for this year’s extra-spooky Forbidden Newberry, I realized that the library holds two extraordinary printed versions of the inescapable Dance of Death. Every version of this epic cycle–from medieval murals showing a literal chain of deadly dancers joining hands with their prey, to single illustrations of each personal death–levels the social hierarchy playing field. Indeed, from pope to pauper, it points out, often gleefully, that everyone bites the dust eventually.

The most famous Dance of Death book is Hans Holbein the Younger’s 1538 set of forty-one intimate woodcuts. It starts with God Creating and then Banishing Man, and quickly moves on to the demise of various members of the clergy, nobility, and tradespeople. Drums and trumpets abound, but that is the extent of its musical content.

The Newberry copy came to us from important book collector Louis Silver, and was owned in the seventeenth century by another artist, Conrad Meyer, whose portrait and initialed bookplate appear in the front. Meyer was obviously inspired by this volume, and went on to publish his own, with a few multimedia tweaks (see example in the slide show below).

Indeed, our 1650 Dance of Death has sixty large copper engravings by Meyer, with some of their order and compositions indebted to Holbein. Perhaps even more extraordinary than this expanded cast of characters, at the end there are not one or two, but eight different Dance of Death songs, all complete with sheet music. There’s number 8, a German dirge entitled rather direly as “A Serious and Threatening Warning to the Unrepentant.” (A transcription and translation of the first verse appears below.)

So, now that we had the lyrics and the music, how could we play it? Musical notation was notoriously difficult to print and looked very different in 1650. Then there were the issues of multiple singers’ parts and correct tone. Each of the eight songs had a different directive, from Mild to Indignant. We decided we wanted to go with the eighth one, given its unusual attitude and direct appeal to the listener. But again, how would we bring it to life?

Enter music historian Eleanor Walters. In just a few weeks, she transcribed it for the nearby St. James Cathedral Choir to record, with the generous help of the Director of Music, Stephen Buzard, who also updated the opening measures. As Eleanor noted, by 1650 women were often included in singing ensembles, usually taking the cantus or alto parts when they were not too low (as here), leaving the tenor and bass(us) to the men. Two countertenors also sang alto for this recording, and all the voices commingle beautifully to create the sound of a reprimanding dirge from across the centuries. Listen to the stunning results of this collaboration here:

While not as syncopated as Spooky Scary Skeletons, or the 1929 Skeleton Dance, this Dance is a real slice of life (and death) from 1650!

Transcription and translation of the first verse:

Achtes Gesang (Eighth Song)

Ernsthafftes und betrohliche (bedrohliche) warnung an die Unbußfertigen (Serious and threatening warning to the unrepentant)

Nach der melodey des 6. Psalmens. (To the tune of the 6th Psalm)

Ihr bößgearte Kinder

Und herzverstokte sünder

Vergiftest Naterzücht

die ihr nur böses heget

Und nicht mit ernst erweget

zeit g[e]wüssen und gericht

Translation:

You wicked children

And heart-hardened sinners

You poisonous offspring of vipers

who harbor only evil

And do not seriously consider

time, knowledge, and judgment.

Suzanne Karr Schmidt is the George Amos Poole III Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at the Newberry.