We may never know who painted the Newberry’s recent and very mysterious gift from a onetime New Bedford whaling family, a colorful 48 foot-11 inch scroll full of charming details in watercolor. But after some careful looking, we have a pretty good idea of when it was made!

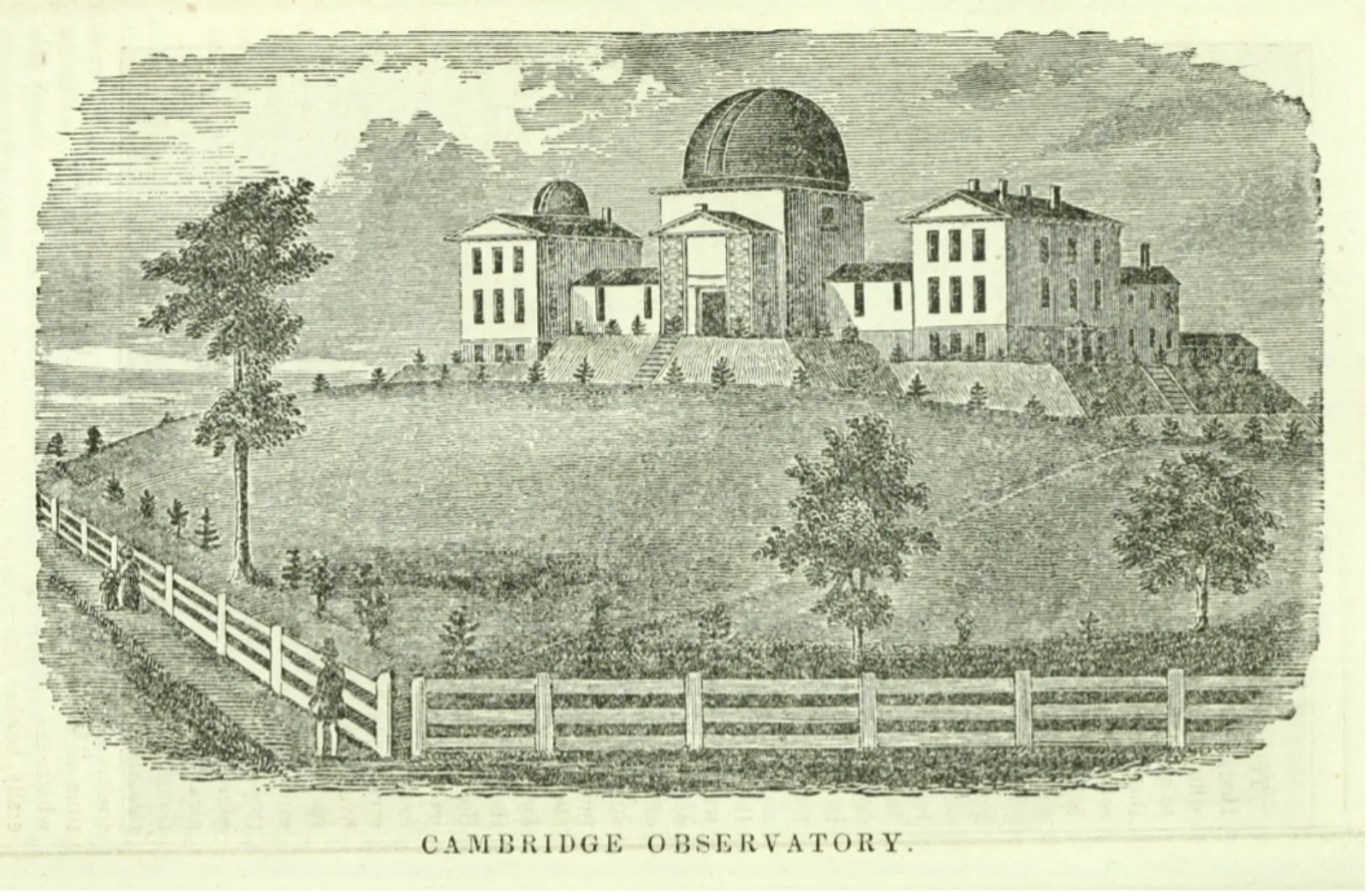

After our Newberry Book Fair impresario Dan Crawford brought the scroll to the attention of the Curator of Modern Manuscripts, Martha Briggs, this summer, she immediately pegged it as being by a mid 19th-century American amateur. But what decade? Could the buildings give us a clue? The lighthouses and the architectural folly near the beginning seemed specific enough to help. But, based on an early woodcut (that might have been available to the artist), it was a distinctive edifice on a different hill that turned out to be the Harvard College Observatory, founded in 1839. So far, so good. Now we knew the scroll could not possibly date any earlier than that.

Yet the real tip-offs were the scant patches of writing in the unsigned and undated scroll. Four of the five circus carriages in the landscape leading up to the Harvard observatory bore the name "Barnum." P.T. Barnum, of course, would be known for "The Greatest Show on Earth," i.e. the Barnum and Bailey Circus. But the museum director and showman extraordinaire did not join forces with Bailey before 1881, a date that seemed late for this scroll.

One final marking gave the necessary clue to date the scroll before 1871, the name inscribed on the saddle of the larger elephant: "TIP SAIB," who was usually known as "Tippo Sahib". This Indian elephant weighed about 9,000 pounds and had the first set of tusks seen in America. Likely brought to the United States around 1824, he enjoyed a long life in show business as a "performing" or "trick" elephant until his much-lamented demise in 1871. He is said to have saved the life of one trainer, attacked or killed a different trainer, and interrupted a surprised group of loggers in the Delaware river.

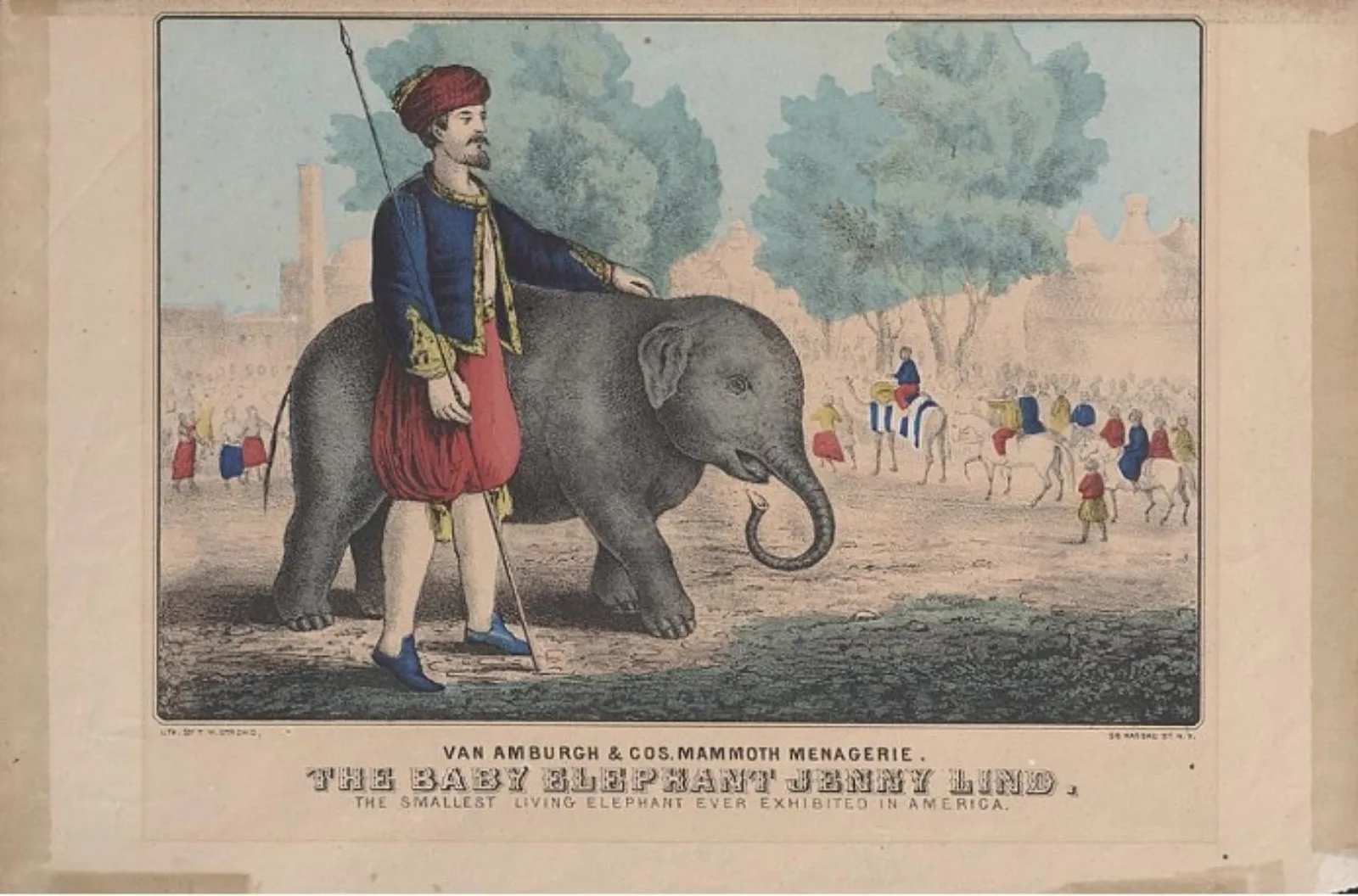

But Tippo does not appear alone on the scroll. The smaller elephant attached by reins to his harness is very likely "Jenny Lind, the Tom Thumb" elephant also headlining Isaac Van Amburgh's Golden Menagerie in 1868 and 1869. Her name is a nod to Barnum, who was also a business partner with Van Amburgh. Beginning in the 1850s, he oversaw a major US tour of the "Swedish Nightingale" opera singer Jenny Lind, as well as touring the original dwarf Tom Thumb. As a result, he made all of them rich and household names. As Barnum foresaw, the rare sight of a baby elephant offered as much public interest as virtuoso soprano, or a miniature Napoleon.

The Barnum and Van Amburgh partnership recently turned disastrous however, as many animals were housed in Barnum's Museum during the fire of March 3, 1868. The March 28 Great Golden Menagerie tour that kicked off only a few weeks later nonetheless was billed as a glamorous attempt at reinvention of Van Amburgh's Mammouth Menagerie, now featuring golden chariots and a salamander bear named "Fire Imp" who survived the fire. "Tippo Sahib" and "Jenny Lind" appear to have overlapped for two seasons of the mammoth menagerie, from the first mention, in March 28, 1868, with notes in the press the next spring making the last time they are mentioned together. Perhaps by then, "Jenny" was no longer considered a baby.

Going by their joint public appearances, the painting seems likely to have been painted in March 1868 to July 1869, or very soon thereafter. But can we get even closer to an actual date? The New York Clipper also mentions stops by the Golden Menagerie in New Haven, Hartford, and Providence in May 1868, and Lowell Massachusetts on the 16th of July, 1868. Perhaps it was also that July when the artist saw the parade, with its golden chariots of musicians blaring and its elephants marching as it passed by Cambridge (only 30 miles to the south of Lowell)? We cannot even be sure if the scroll represents a real event witnessed by a New England resident, but the amount of detail suggests some knowledge of the area. There is even a separate animal parade (with a single elephant) on the scroll that does not mention Barnum, so perhaps it was made by someone who desperately wanted to run away with the circus...

We are thrilled to share this amazing object and the new facts we've gleaned about it. However, as the pictures show, the painting will need a significant amount of conservation before it can be used in the reading room. Eventually, the entire scroll will be conserved and digitized, and, finally ready for our readers to experience in person. But for now, other locations and details on the scroll will no doubt ring a bell for history and circus buffs, and so we urge you to help us identify them!

About the Author

Suzanne Karr Schmidt is the George Amos Poole III Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at the Newberry.