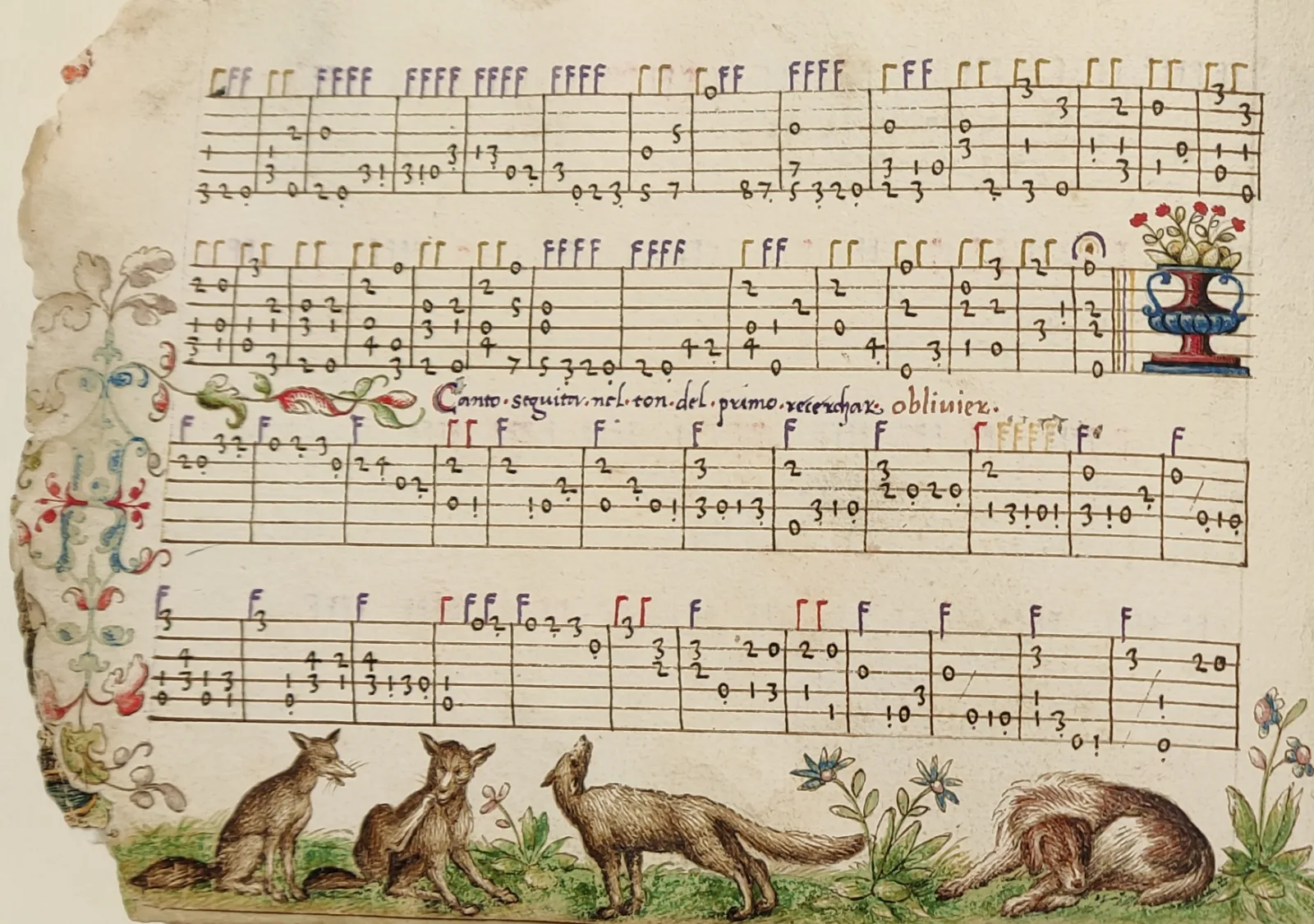

Like certain infamous, fox-themed earworms, printed images have a habit of reappearing in the most surprising places. One of these foxholes is a musical manuscript at the Newberry Library from 1517. The text of this manual and score for lute players was created by the Italian composer Vincenzo Capirola (1474–after 1548). Unusually, its colorful border landscapes are full of squabbling animals, mythical beasts, and a few shepherds. Better known to music historians than art historians, their painter remains anonymous. These creatures were clearly copied from a variety of printed sources, including a famous monkey by Albrecht Dürer, but others also seemed very familiar…

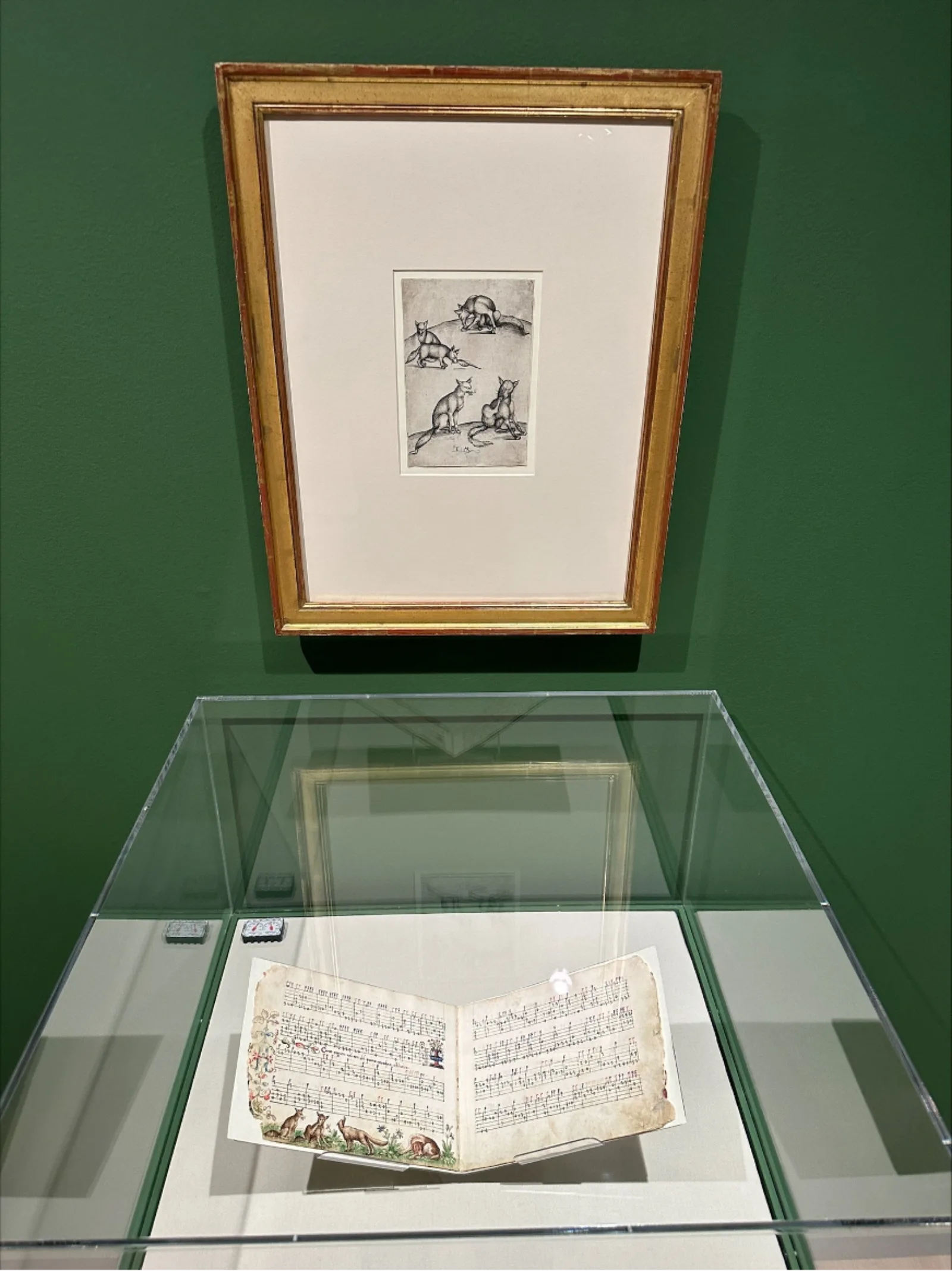

Only recently, I realized that the book was citing one of my favorite engravings from the Art Institute of Chicago! This brainstorm hit when Chazen Museum curator James Wehn mentioned his upcoming exhibition about fifteenth-century German goldsmith and printmaker Israhel van Meckenem. An enterprising businessman who harnessed the multiplicity of print, he spent much of his career copying and republishing works by other artists (at a time when copyright didn’t apply in modern terms).

An original engraving he made around 1490, The Five Foxes stands out among van Meckenem’s rare ornamental works, and the direct connection to the Newberry manuscript nearly thirty years later shows how influential his own images became. Happily, James Wehn was able to borrow both the relevant pages of our manuscript and the Art Institute's print for the show, and they are currently on view together!

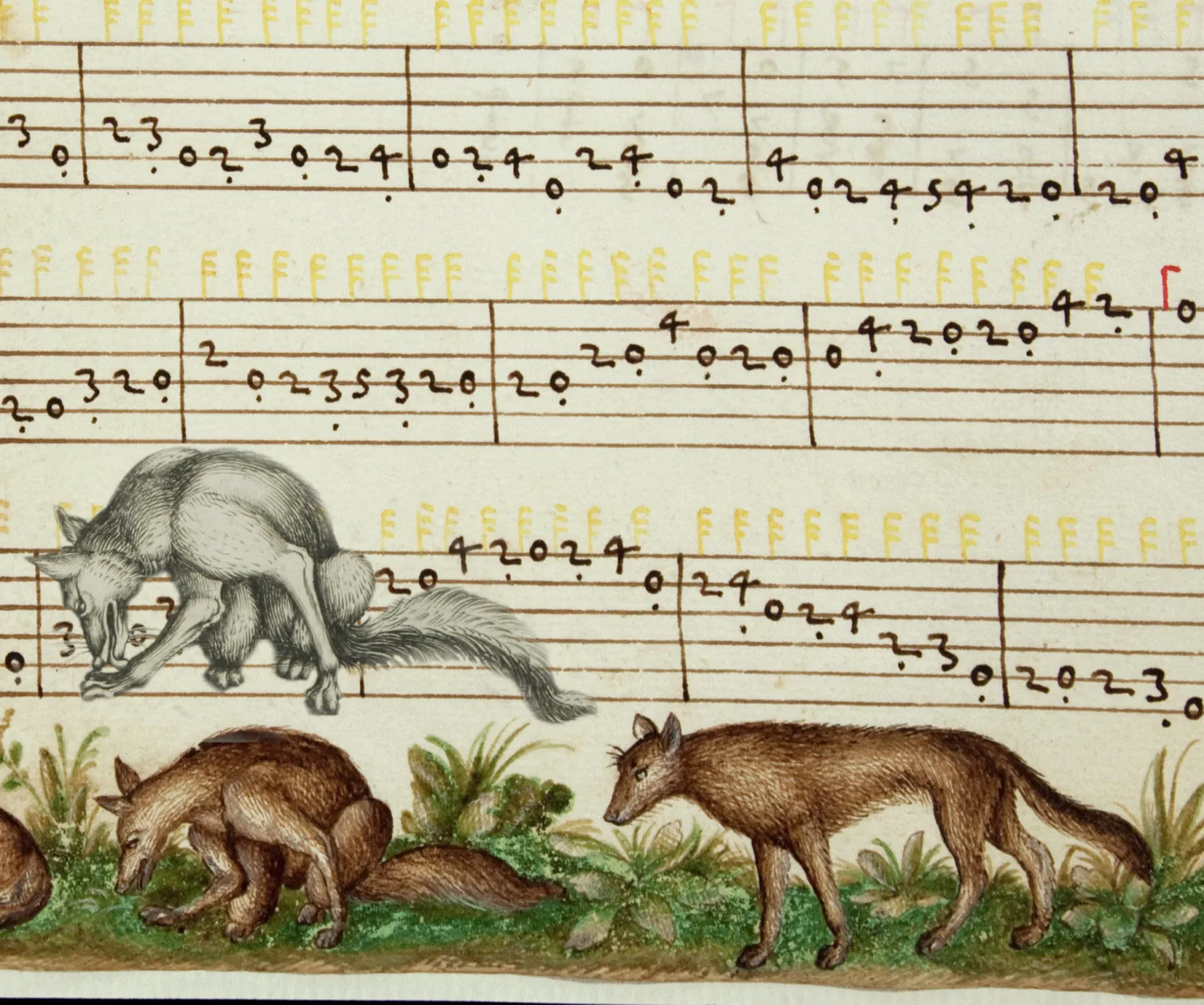

How closely did the Italian artist copy van Meckenem’s print? Three of the five foxes appear in it, two on the page on display, and another later in the same section. They appear in the same direction as the engraving, confirming that the anonymous artist was looking at an impression of the print itself, not a reversed copy or preparatory drawing. The scale is close, but not exact; there are enough compositional differences to show that the artist redrew the foxes freehand rather than tracing them from the printed sheet.

The color also differs; van Meckenem’s engraved lines are finer than the manuscript’s brush strokes, but the print is in black and white, as opposed to brownish-red toned fur. The illuminator picked three of the largest and most lively foxes, repeating the first two as a pair. While they have no direct connection to the score inscribed above, the animals do make some noise. The fox on the left’s mouth hangs open in one-sided conversation, while the fox on the right scratches using a rear leg.

On the second manuscript page (not on view in the show), the van Meckenem fox is more isolated, but fully engrossed in self grooming, licking a front paw clean. The painted foxes are simpler creatures, with less flamboyantly decorative tails, while the sidelong glances of the engraved ones make them cannier and slightly more sinister. Both sets are unforgettable, and reuniting them within their original artistic and historical context has been an utter joy!

This groundbreaking exhibition and catalog, Art of Enterprise: Israhel van Meckenem’s 15th-century Print Workshop, is on view at the Chazen Museum of Art in Madison, Wisconsin, through March 24. After that, come by to look at the manuscript back at the Newberry!

About the author

Suzanne Karr Schmidt is the Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at the Newberry.