On May 24, 2022, I rented a van, stuffed it with almost 50 bankers’ boxes of family archives, and drove to the Newberry Library, where I delivered the boxes into the hands of Alison Hinderliter, Lloyd Lewis Curator of Modern Manuscripts and Archives, and her team. It was the culmination of a journey on which I’d embarked almost three decades earlier.

While preparing my mother's home for sale after her death in August of 1994, I made a discovery in the attic. There, tucked into the corners and cobwebs under the pyramidal-sloped ceiling, we found gems of family—and 20th-century—history. In boxes, bags, and a cedar chest that once belonged to my Grandma Gartz lay a trove of diaries, letters, documents, scribbled notes, photos, and much more that had lain entombed for decades.

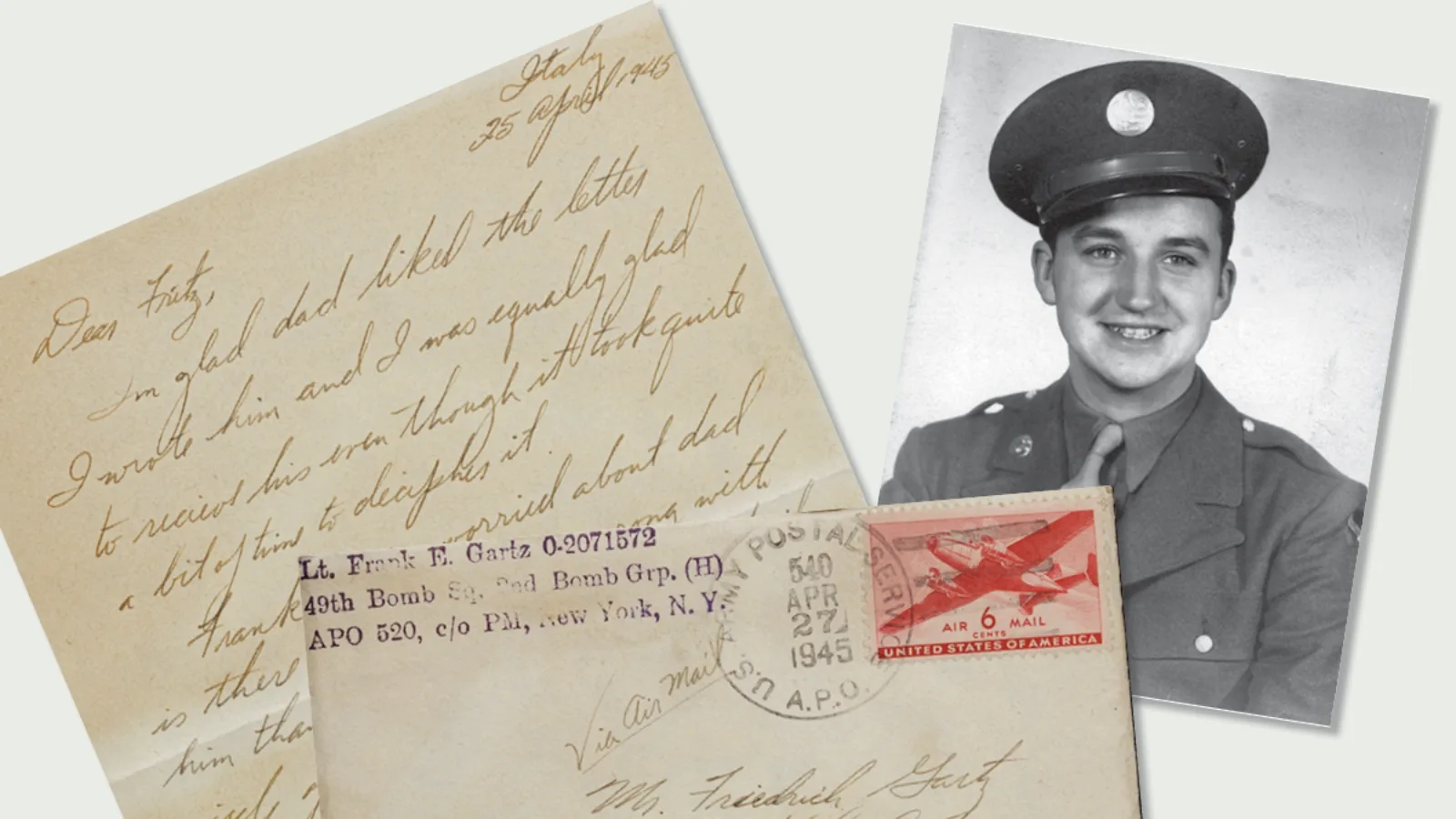

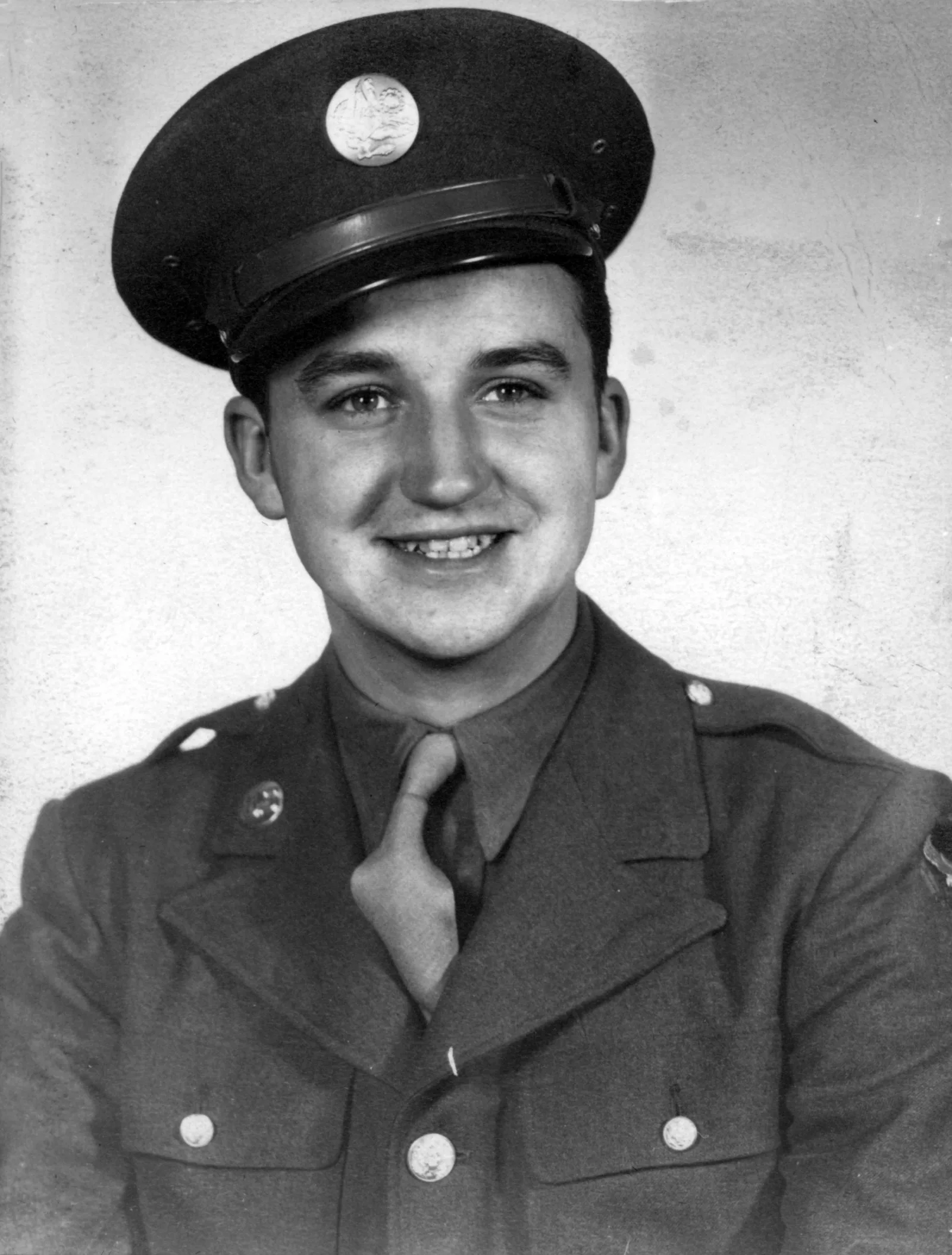

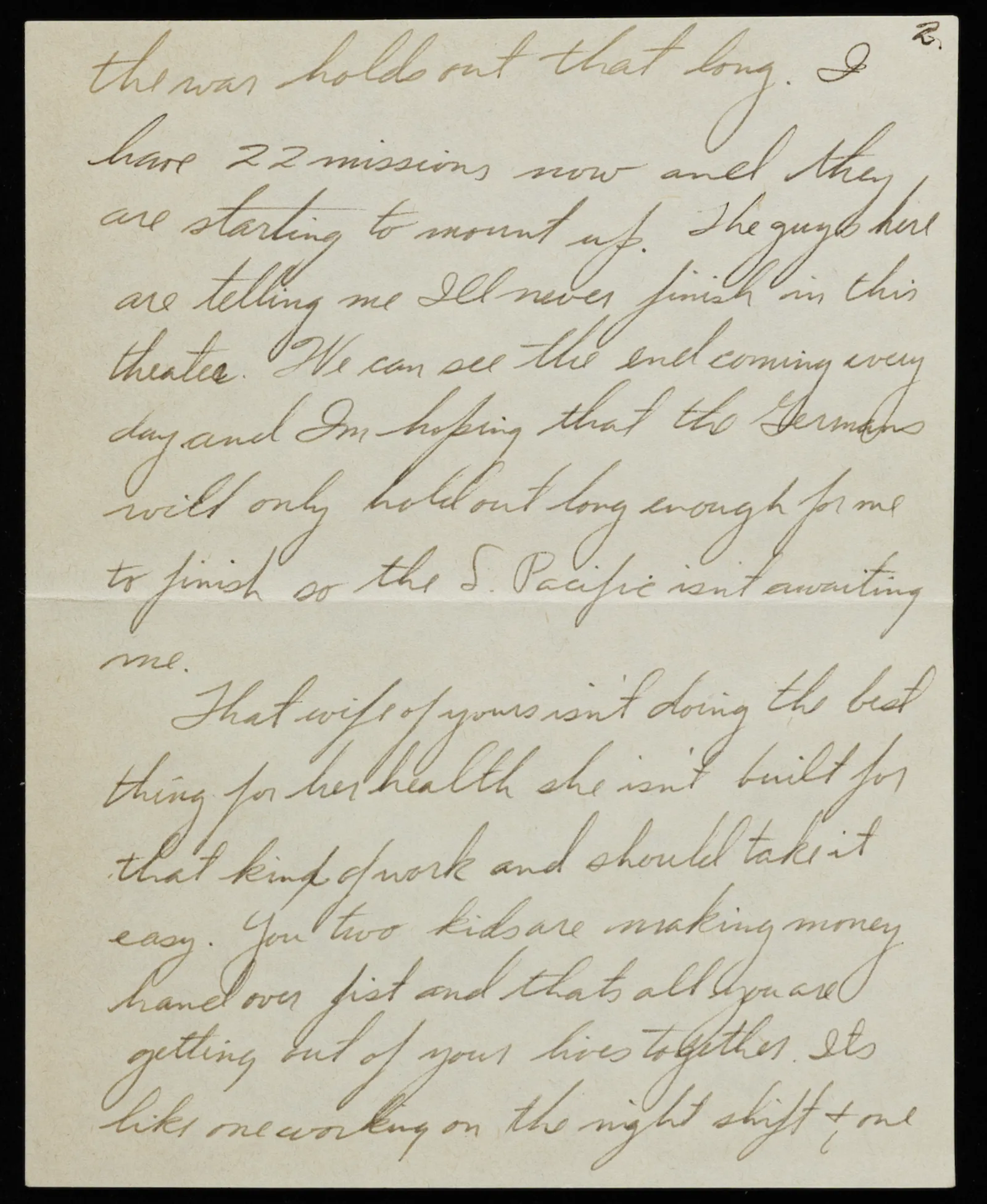

There were 70 years of letters sent between my paternal grandparents and friends and family from their homeland (what is today Romania); nearly 300 letters exchanged with my uncle, Lt. Frank Gartz, a B-17 heavy bomber navigator in World War II; diaries dating from 1910 to the 1980s; family diplomas earned in America and Europe; my maternal grandmother’s mental health records; and hundreds of photos dating back to the 1890s, along with slides and film.

My mother’s diaries, from 1927 through the 1980s, trace the arc of the 20th century and its effects on my family’s personal lives. She wrote about living through the Great Depression and, later, about the changing racial demographics of our neighborhood of Chicago’s West Garfield Park in the 1960s. As the journals move into the 1970s and ’80s, they reveal my mother’s fury at the changing mores wrought by the sexual revolution, and the conflict between older and younger generations.

At the time of the “house-cleaning,” these details were unknown to me and my brothers. We had no time to look closely at our discoveries, so we quickly noted the provenance of each item and sorted them into bankers’ boxes. We filled 25 boxes, which came to be stored on the second floor of my garage.

Those boxes sat in my garage while I focused on running a household and raising two boys. Almost eight years passed when an insistent little voice in my head started nagging me: What might be in those letters and diaries? What secrets might they reveal?

I succumbed and hauled out the box with World War II letters to and from my Uncle Frank “Ebner” (my grandmother’s maiden name). I’d never met Ebner, so I eagerly began reading. Like the reel of an old movie, the world of 1940s homefront Chicago, along with the life of a young man thrust into basic training and then Army Air Corps preparation, unspooled before me.

I was hooked. I wanted to know more, so I started “the dig.” I was elated with each discovery, like an archaeologist unearthing clues to the past.

Next, I turned to my parents’ letters and diaries. Mom had started a journal when she was ten years old, in 1927. They begin superficially enough, describing the weather and schoolwork. But as time goes by, her increasingly lucid, vibrant writing gives great insight into major events like the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, to which she won free admission as part of a writing competition run by the Chicago Daily News.

For my mother’s family and so many others, the World’s Fair was a temporary diversion in the midst of the Great Depression. At least 50 percent of Chicago machinists lost their jobs during the Depression, Mom’s father among them.

Her proud Austrian-born parents had to accept food aid, which my mother described as “nothing fresh: cheese, stale coffee, canned tomatoes.” After one of the few times he was called into work, her father came home with two missing fingers, chopped off by the machinery’s merciless, unrelenting motion. Mom wrote, “My face turned white, and my knees buckled. Papa lost two fingers [in Austria] when he was twenty-two; now another two. Goodbye guitar.” A talented musician, her father reversed the guitar and learned to play with his right hand on the fret board.

For me, the most thrilling entries were those describing Mom (Lillian) falling in love with my dad (Fred). She met him (for the second time) at a dance in May 1941, and fell instantly in love. “Oh, it was heavenly,” she wrote in her diary. “He knows all the little innuendos of kissing, and I ain’t so bad m’self, if I do say so. We kissed for about an hour and a half. . . . He is definitely the man I want to marry.” She continued her ecstatic entries for the next year, when he finally confessed his love in May. They married November 8, 1942.

The letters exchanged between my parents chronicle changes in their relationship as well as the wider social and cultural context of the 1950s and ’60s. As I scoured my family archive, two stories emerged: the unraveling of my parents’ once-happy marriage and the transformation of our West Side community due to racist real estate practices.

The transition of the neighborhood from virtually all white to virtually all Black started after a neighbor died, and the house was sold to a Black family, who moved in on June 22, 1963. White flight began in earnest. My parents stayed. Two months later, my mother recorded in August 1963, that two-thirds of our street had become home to African Americans. That same month, Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington.

It wasn’t long before we were among the few whites left in West Garfield Park. In June 1965, when the neighborhood was majority Black, my grandparents, who lived half a block east (at the corner of Keeler and Washington Boulevard) summarily announced they were moving to Villa Park (a suburb of Chicago) and handed over their six-flat to my stunned parents. Shocked by this sudden move and unheard-of generosity, my parents decided to rent the six-flat rather than sell it.

The next month I saw a “For Sale” sign on a beautiful but run-down Victorian house next door to my best friend, Peggy. I told my parents about this house we’d always admired on our many visits to Peggy’s apartment. Our whole family toured the house, fell in love with it, and my parents bought the 65-year-old fixer-upper. It was our first single-family home. Now we owned four properties: three rental properties on the West Side and a large home in need of serious updating five miles north.

Over the next 20 years, Mom documented the intense efforts on this North Side home as well as the nonstop work to keep up their buildings. Overcoming previous prejudices, they rented for the first time to African Americans, working seven days a week to provide good housing in a community slipping into poverty and neglect.

As I unloaded the bankers’ boxes last May into the welcoming hands of the Newberry’s Alison Hinderliter and her team, relief washed over me. I’m thrilled and grateful that the Gartz Family papers will provide vast resources to researchers of the 20th century, as well as insight into the lives of three generations of ordinary Chicagoans. It’s often the quotidian details of daily life, love, and loss—recorded in this collection—that reveal the human side of history and bring our lives into sympathy with one another.

About the Author

Linda Gartz is an Emmy-award-honored television producer, blogger, essay writer, and author of Redlined: A Memoir of Race, Change, and Fractured Community in 1960s Chicago. An audiobook of Redlined will be out in April 2023.