What was race like in the European Middle Ages? This is one of the key questions raised by Seeing Race Before Race, the Newberry’s current exhibition exploring the roots of race and racial thinking before 1800. It is an especially important question for us to think about today, a time when white supremacists actively use medieval symbols and ideas to support their violent agendas. In large part, this has happened because scholars have not really thought about race at all in medieval Europe until the past three decades or so. Before then, they too operated under the assumption, created by nineteenth-century nationalist historians, that Europe between 500 and 1500 CE was an exclusively white space.

But the sources themselves tell an entirely different story. As many medievalists have shown in recent years, these texts, artworks, and material objects show Europeans in the Middle Ages describing, thinking about and, most importantly, making race to make sense of themselves, their place in the world, and their access to power and resources. Understanding what race meant to medieval people, then, can help us more clearly see what race means for us now.

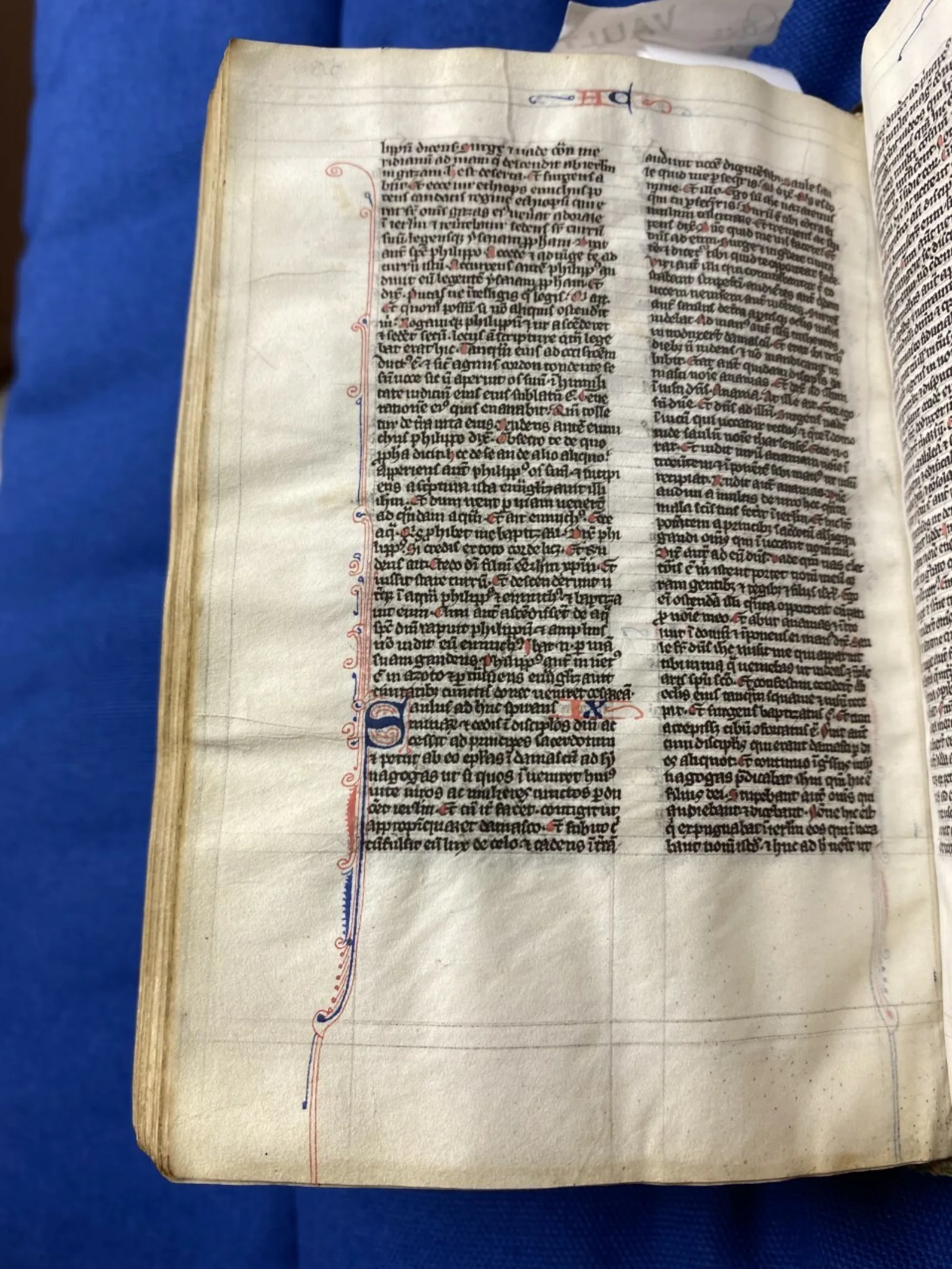

First and foremost, race was undeniably present in medieval Europe, when many white Europeans lived alongside people of color. But even those who didn’t would have encountered many people of color in the Christian Bible, such as the Ethiopian wife of the patriarch Moses (Numbers 1: 21), the three "Wise Men” who brought gifts to the Christ Child (Matthew 2: 1-12), and the Ethiopian eunuch converted by the Apostle Philip (Acts 8: 26-40) [Figure 1]. Just like in real life, this diversity could cause tension, as acknowledged by the “black and beautiful” Bride in the Song of Songs, who recognizes that her skin sets her apart from other women in ancient Israel: “Do not think that I am dark because I have been burned by the sun, daughters of Jerusalem” (Song of Songs 1: 4-5). Since the Bible was the foundation of virtually all intellectual and artistic culture in the Middle Ages, these figures were represented across all types of media—commentaries, sermons, visual art, miracle stories, and more—ensuring that the idea of race was firmly planted in the European imagination.

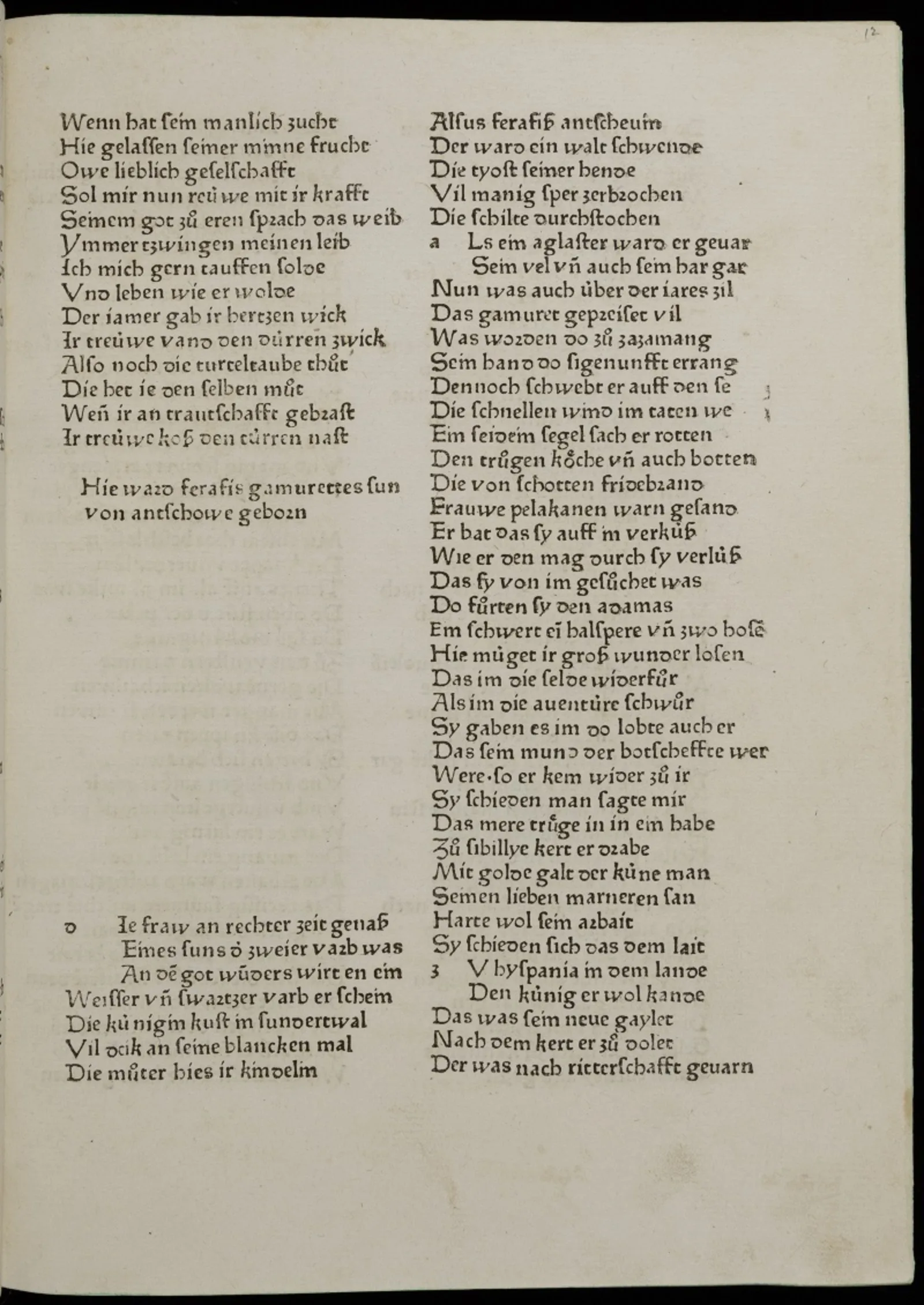

Next, the medieval idea of race was much more flexible than our own, which is based primarily on skin color. On the contrary, people in the Middle Ages used a variety of visible differences—geographic origin, language, religion, cultural practices, dress, class, and more— to place people into categories. For example, the artist (or artists) who created the image of the Adoration of the Magi in the Newberry’s copy of The Mirror of Human Salvation, decided to use a turban-like crown and a bushy dark beard, not skin color, to indicate that one of the Magi came from Africa. [Figure 2]

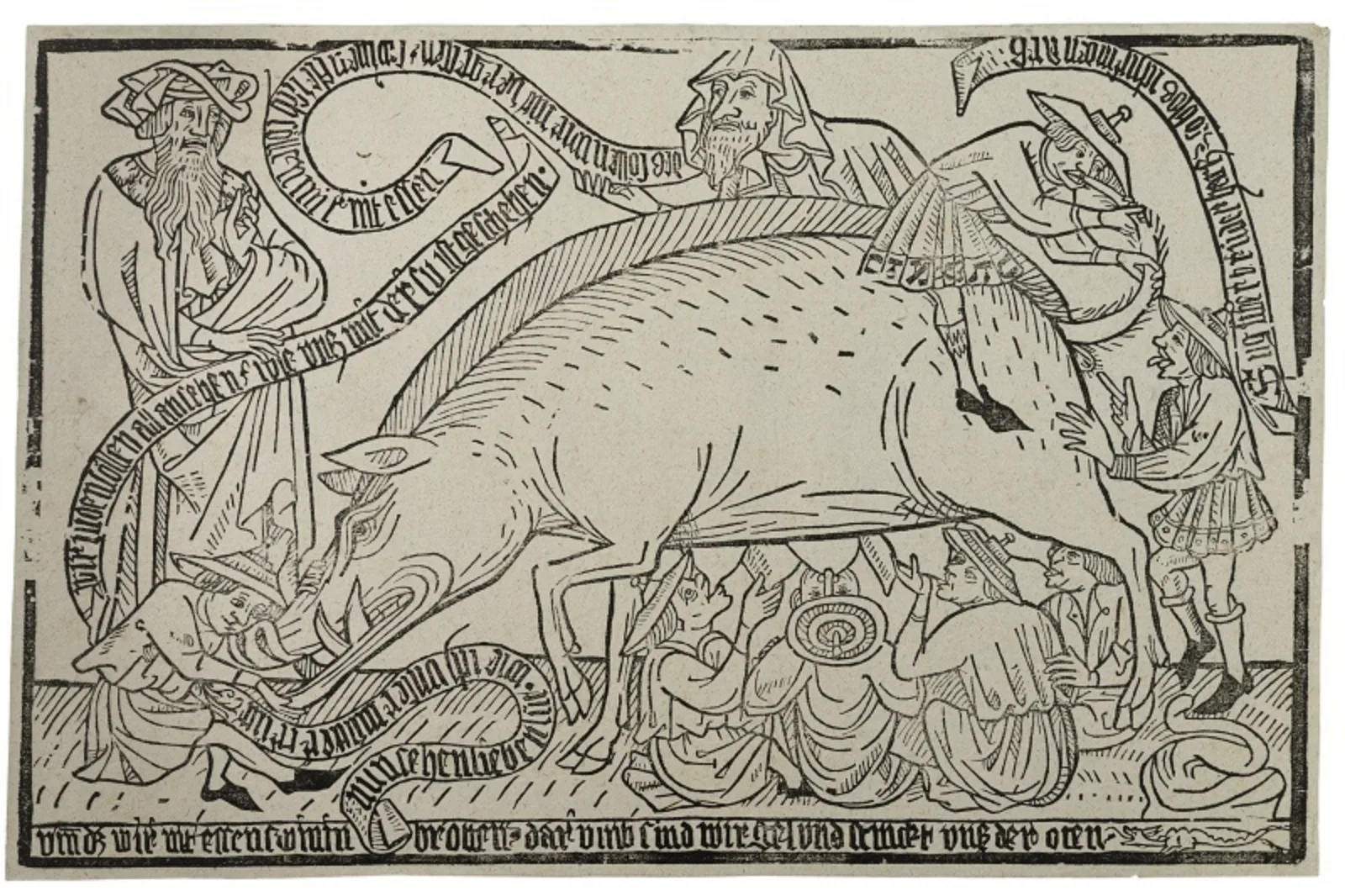

The flexibility of medieval race made it a useful tool for explaining things about the world and its peoples. Take, for example, Feirefiz Angevin, a biracial character in Parsival, a twelfth-century Arthurian romance. [Figure 3] The son of a white Christian knight from Europe and a Black Muslim queen from Africa, Feirefiz’s skin and hair are described as a patchwork of black and white areas “like a magpie.” His appearance reflected his complicated personality, which included some qualities Europeans associated with themselves (courage, fighting prowess, courtesy) and others they associated with non-white “Others” (ignorance of Christianity, pride, obscene wealth). Even though medieval readers would have known Feirefiz was not an accurate portrayal of a biracial person, they would have seen him as proof that there was a concrete connection between one’s physical appearance and one's character and capabilities. Centuries later, this idea became the foundation for nineteenth-century biological racism and racial profiling today.

Finally, race in medieval Europe could also be violent and dehumanizing, as can be seen in the example of medieval Jews, the most well-documented victims of medieval race-making. Many Christian religious authorities, concerned that the physical similarities between Jews and Christians might promote intermarriage, worked diligently to define Jews as a distinct category of human beings. They did so by spreading vicious false stereotypes about their appearance, forcing them to wear special clothing, and mocking their religious practices. [Figure 4] Later, this race-making was used to justify the widespread oppression, expulsion, and murder of Jews and their communities across the continent. Centuries later, Europeans used these same tactics to marginalize and oppress non-European peoples (Indigenous Americans, Black Africans, East Asians, etc.) they encountered in colonialism.

Learning to see race in the European Middle Ages helps us understand how race was used to create distinctions and manage power relations before its most recognizable symptoms existed (European colonization, institutional chattel slavery, and a scientific definition to justify them). That knowledge, in turn, is essential for overcoming systemic racism and white supremacy. Medieval race helps us to see not just how race has evolved and changed, but also how it actually works. The better we know this, the more effectively we can unmake race and heal from its harmful legacy.

About the Author

Christopher Fletcher is Assistant Director of the Center for Renaissance Studies at the Newberry Library.

The Seeing Race Before Race exhibition is on view at the Newberry through December 29.

Learn More About the Exhibition